Chris Gratien, Ph.D. Candidate, Georgetown University

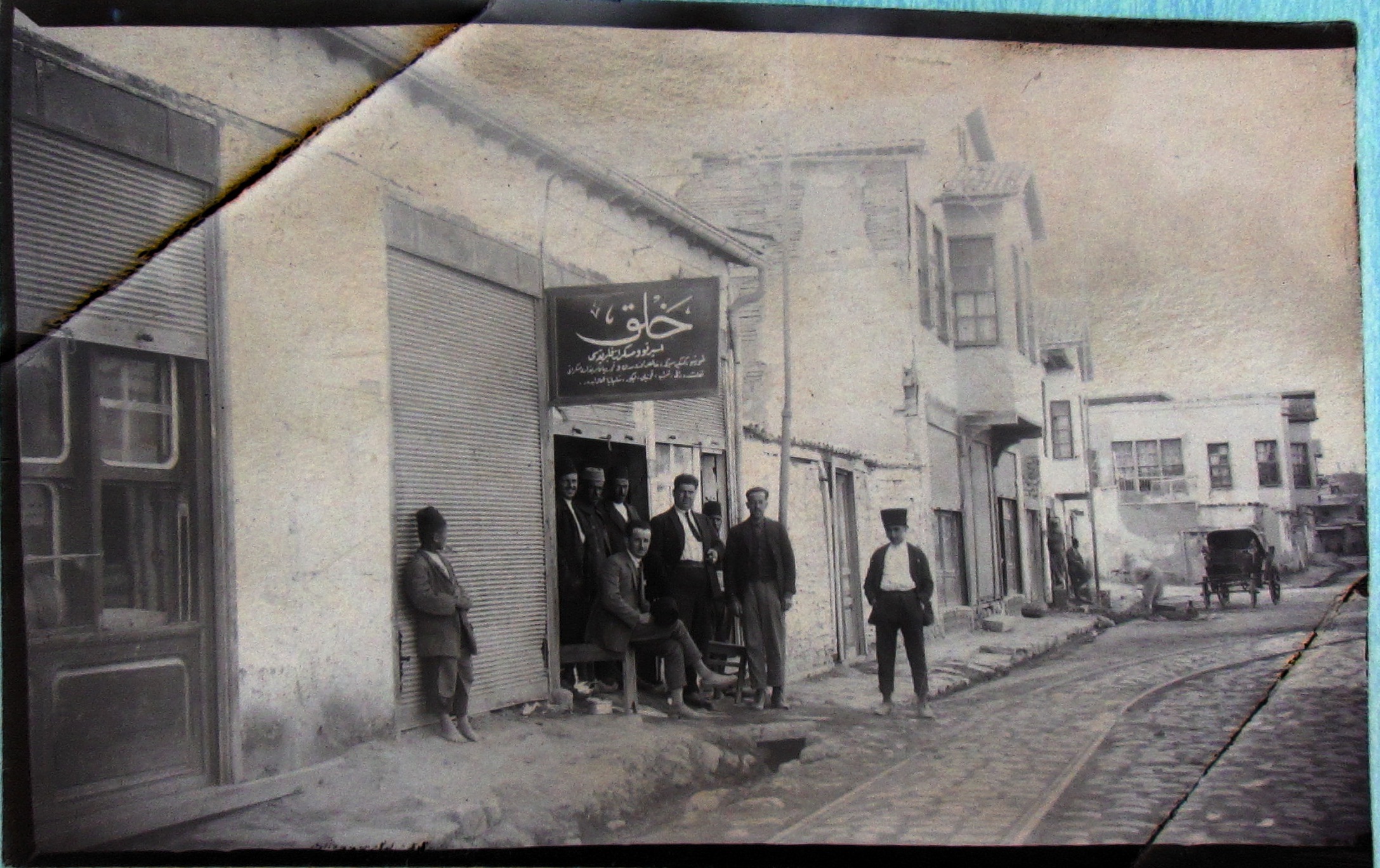

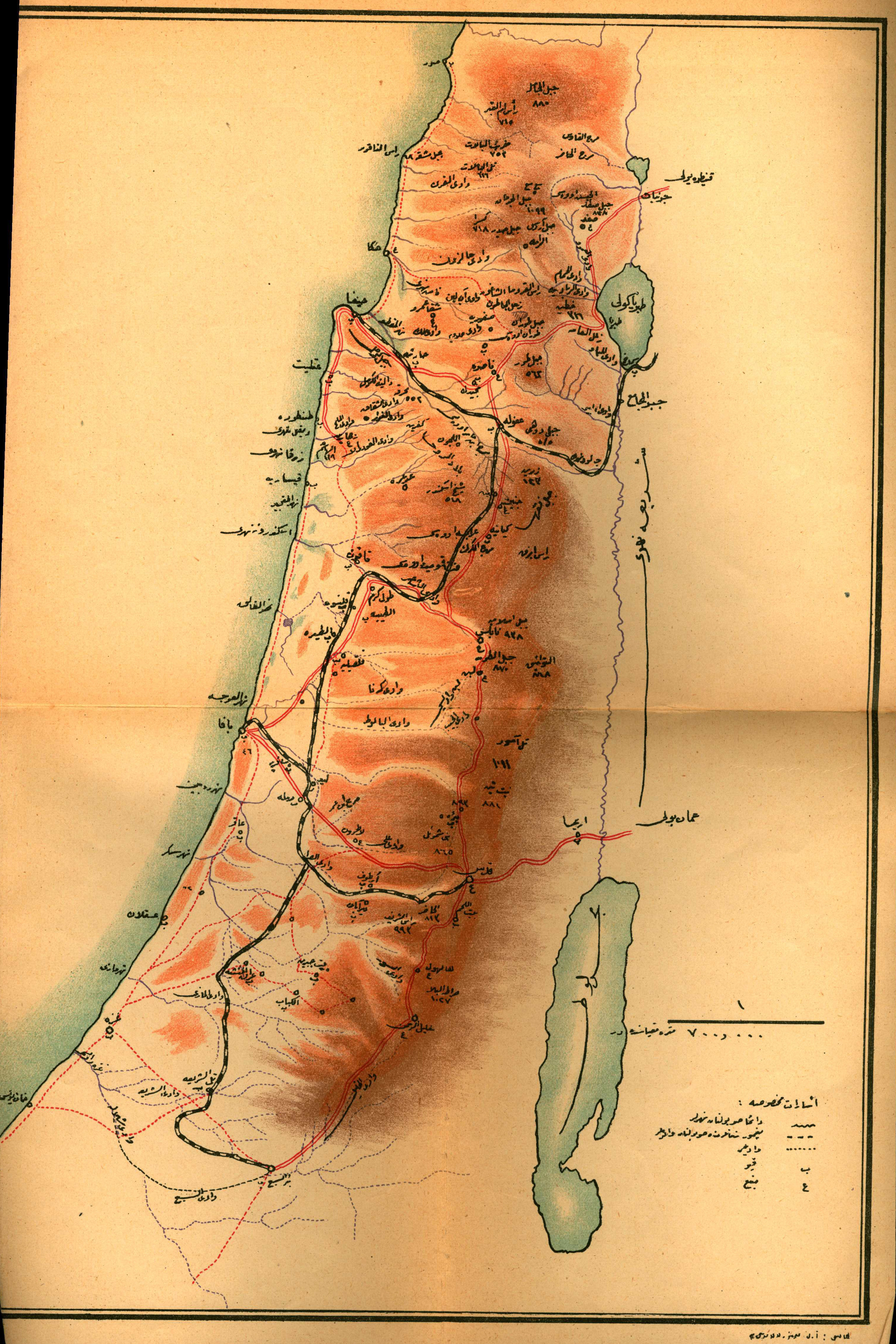

![]() |

| Yörük Encampment in the Taurus Mountains from Edwin John Davis, Life in Asiatic Turkey (1879) |

Summer is upon us and as in many summers past, millions will visit the various beaches of Turkey's Aegean and Mediterranean shores in search of fun and sun at popular holiday destinations such as Bodrum, Ayvalık, Fethiye, and Kaş. The warm coasts of modern Turkey are increasingly a vacation destination for those looking near and far for excitement or relaxation. The phenomenon of beach culture and many of the things that come with it are historically recent on the global stage; yet, summer sojourns to alternative locations are nothing new. In fact, long before the beach resorts of Bodrum, swarms of seasonal travelers once flocked not towards but rather away from the coasts during the hot Mediterranean summers.

The summer destination of choice throughout the Ottoman period was of course the mountains, where cooler air promised health and respite from the scorching heat of the plains and coasts. While for well-to-do city-folk this might have been a trip to a summer home in the mountains, all segments of society participated in this seasonal migration. In particular, pastoralist communities would move their entire herds and property to a summer pasture referred to as a yaylak (or yayla), where they would set up camp until the passing of the hottest months allowed them to migrate back down to the grassy plains for winter grazing. This seasonally migratory pattern arose out of a symbiosis between geography, climate, and human activity that defined life and politics in many parts of the Anatolian countryside.

Changes in the political, economic, and technological contexts of human society have dramatically transformed the function of the yaylas that nonetheless continue to hold symbolic significance for many. The massive migrations of people and animals have become a thing of the past, and while this has meant an overall decrease in the geographical significance of highland plateaus, people continue to find new ways of making use of these spaces. This short essay offers a historical glimpse at summer pastures and the migrations they encouraged over the course of dramatic changes in ecology within Turkey over the past two centuries complete with a compilation of maps new and old.

As pleasant summer pasture-themed accompaniment to this article, please enjoy Selda Bağcan's rendition of "Yaylalar"

Nomad's Land: Features of Transhumance![]() |

Source: Wagstaff, The Evolution of Middle

Eastern Landscapes (1985) |

The diagram at left from Wagstaff's

The Evolution of Middle Eastern Lanscapes (1985) shows the different possible ways of living in the Middle East and their intersections. Crucial to this model is the point that a community relying entirely on either a nomadic or a sedentary lifestyle or entirely on either cultivation or pastoralism is not as common as a lifestyle comprised of a combination of these different types.

The romantic notion of the wandering nomad whose noble yet rudimentary mastery of nature stands in stark contrast to our modern methods is not without its justifiable appeal but often lacks an appreciation of the sophistication of mobile modes of living. Migratory societies, while lacking some of the institutions of settled or urban society, are nonetheless structured around finely-tuned ecological practices well-suited to various ways of life including the raising of livestock or pastoralism.

Transhumance is a migratory mode of living based on seasonal exploitation of areas of differentiated elevation, namely in the form of migration from a highland summer pasture and a lowland winter pasture. Transhumant pastoralism has historically been practiced not solely in the Middle East but throughout not only Europe, Africa, and Asia but also in the Americas as well with the introduction of domesticated livestock.

![]() |

Source: Wagstaff, The Evolution of

Middle Eastern Landscapes (1985) |

While villagers residing in fixed structures who migrated seasonally are considered transhumant just as well as any, many of the transhumant communities of the Middle East lived in mobile tents (and are often referred in the archival record as "tent-dwellers" for this reason, see

Nora Barakat, OHP #61). The diagram on the right from Wagstaff shows different kind of nomadism with transhumant pastoralism represented by the vertical nomadism at the bottom. Pastoralist communities followed streams and mountain passes to access plateaus (the "summer quarters" or yaylas in our case) where they could graze their livestock and followed similar routes on their return. Thus, the migratory patterns of these communities were tied to the possibilities and opportunities offered by the mountainous geography.

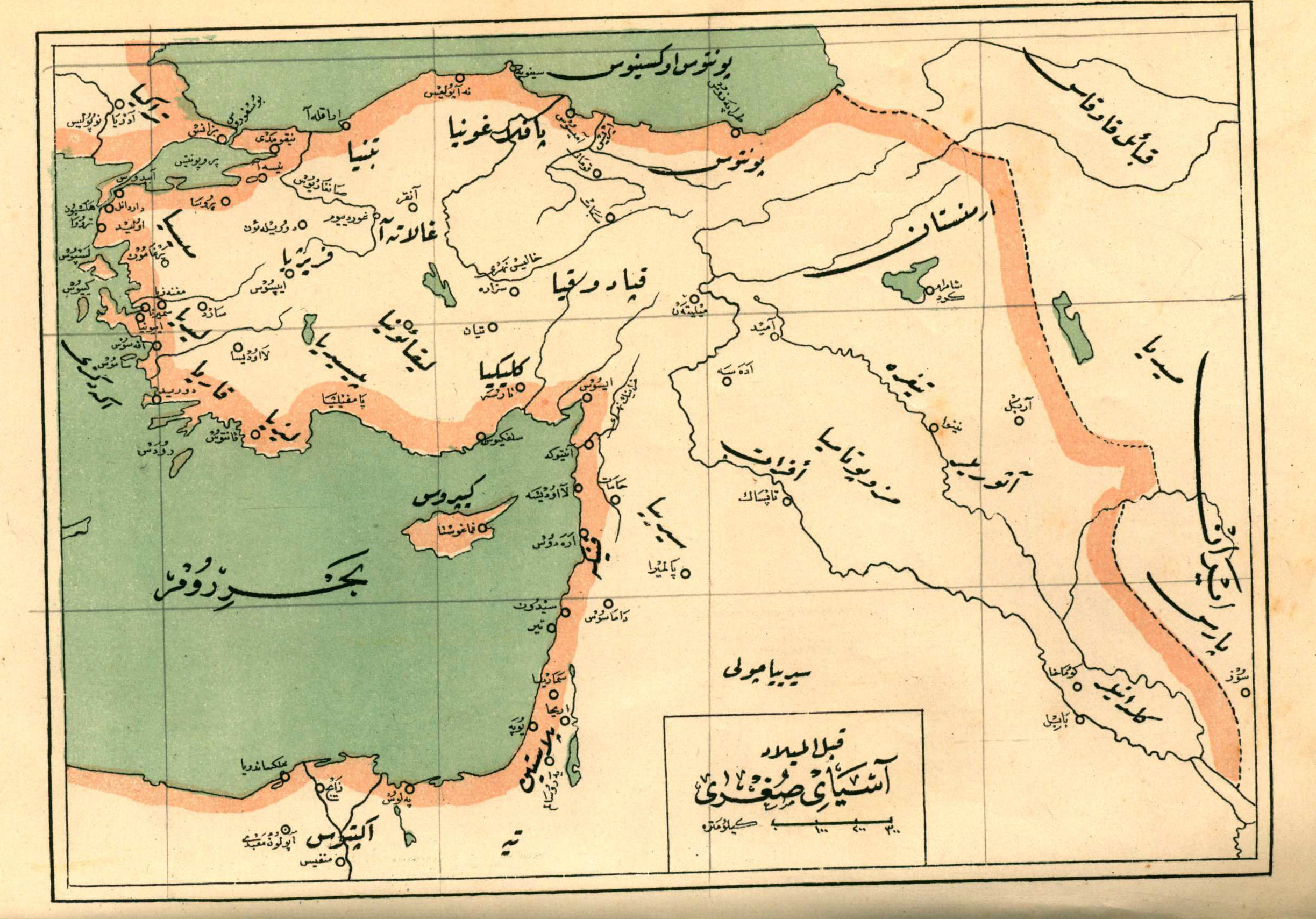

Distances of migration varied depending on the distribution of yaylas. While transhumance could mean moving as short a distance as a few kilometers to a nearby mountain or hill during the summer, some seasonal migrations in the Ottoman Empire entailed the movement of tens of thousands of people and animals over hundreds of kilometers of differentiated terrain. For example, the map below at left shows the different types of migrations in the Adana region that sent pastoralists wintering in Çukurova through the Taurus Mountains far off towards Kayseri, Niğde and the massive Uzunyayla near Sivas. Alternatively, the map on the right shows smaller migration routes in the Antalya region of Turkey, where transhumance remained a viable lifestyle well beyond the late Ottoman and early Republican period when state pressure and economic factors combined to all but eliminate this type of nomadic living.

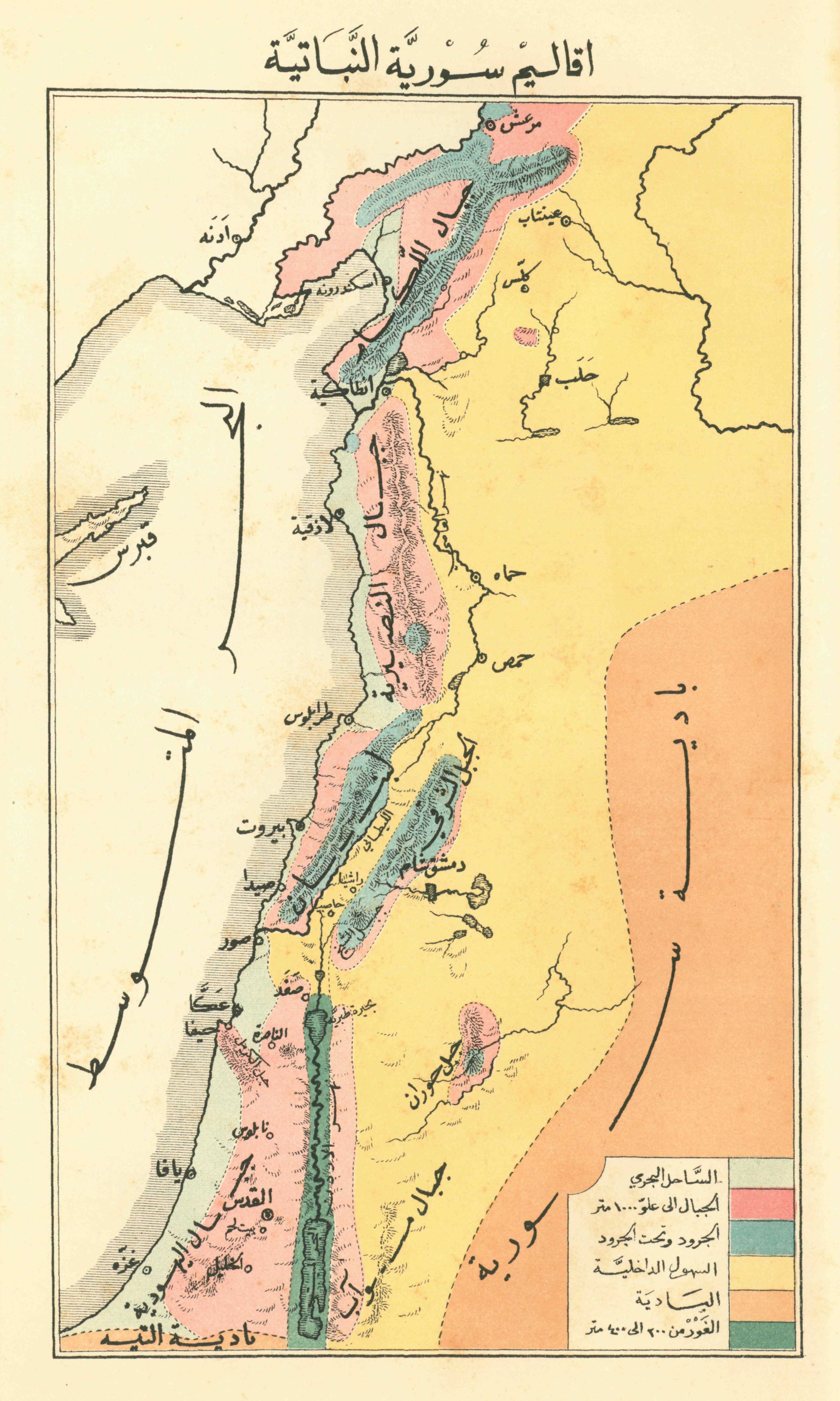

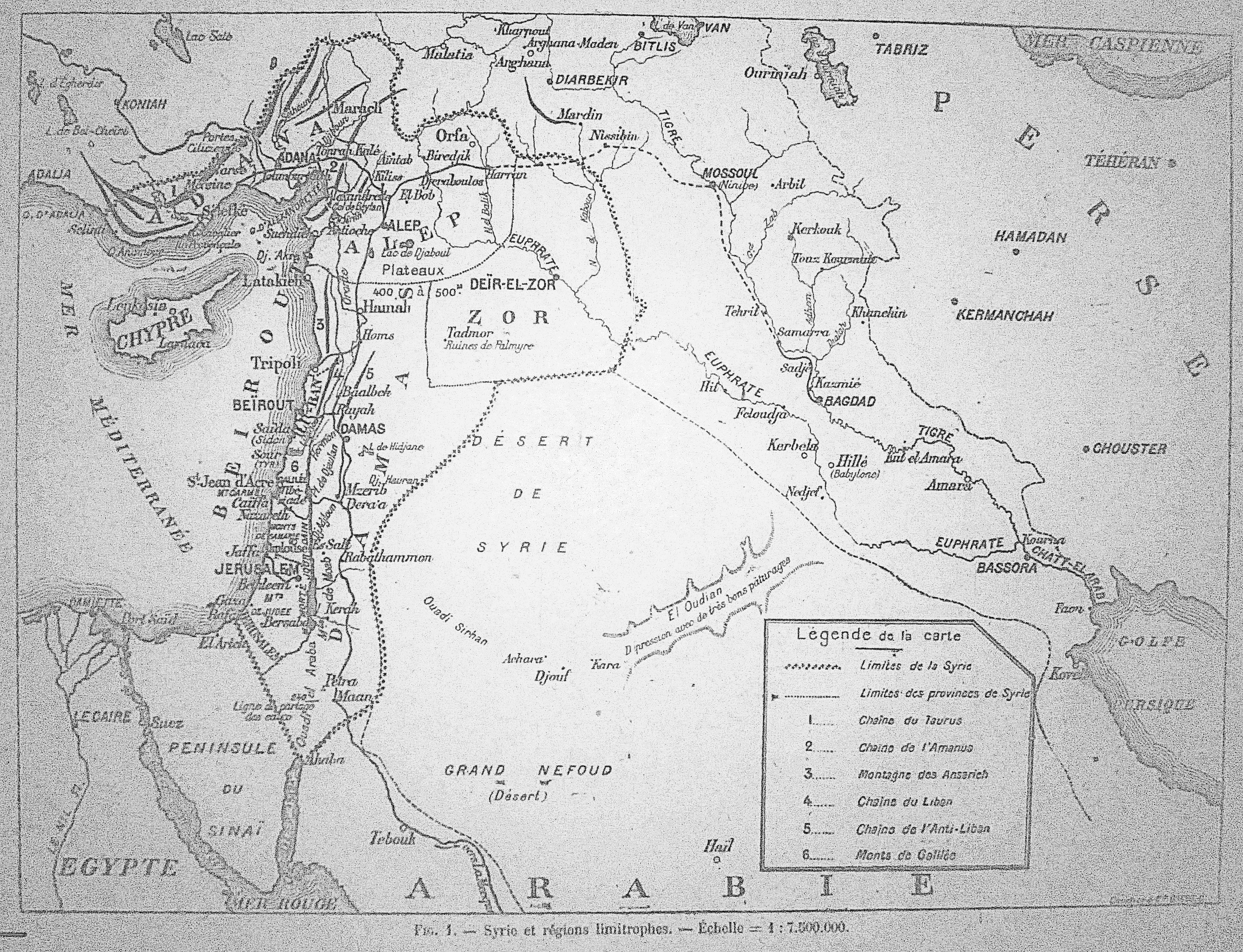

While summer pastures make great holiday locales to beat the summer heat, the function of the type of pastoralism practiced in the Middle East has historically extended well beyond a change of air. Most practically speaking, nomadic living allows pastoralist communities to access more vegetation and utilize lands with insufficient rainfall for sustained sedentary agriculture without irrigation. The map just above on the left illustrates broadly the parts of the Middle East that are unsuitable for dry farming due to insufficient rainfall, and small patches of historically uncultivated land that do not register on this map can indeed be found throughout the former Ottoman Empire. The map to the right shows the resultant distribution of lifestyle in modern Syria, which mostly conforms to the pattern described here although it is influenced by the use of irrigation in some areas.

![]()

Migratory lifestyles not only allow pastoralists to make use of otherwise marginal lands before moving on to another pasture but also allow them to take advantage of seasonal rainfall differences and reduce the ecological burden of their flocks on the grasses they graze so as to effect a more sustainable rate of consumption. The diagram at right shows the seasonal plant growth rates in the Mediterranean. Generous rates in the spring and summer allow for healthy pastures to develop at high elevations where little can grow during the winter. Migrating to access these pastures allows thick grasses at low elevations to replenish.

Of course, transhumance was also widely practiced in regions that were perfectly suitable for agriculture, which points to some of the other advantages of a mobile lifestyle. In times of crisis, mobility offers a form of security, and following the initial instability of the Celali rebellions during the 1590s, the countryside of the Ottoman Empire was certainly a place where the state failed to monopolize violence, leaving villagers vulnerable to the depredations of armed groups also fighting to survive in what

Sam White has aptly referred to as a Climate of Rebellion, pointing to the role of climate variation and ecological disruptions of the agrarian economy in creating this period of instability. White argues that the environmental conditions which created food scarcity and caused village economies to fail favored an outcome of an increase in a move towards pastoralism and a semi-nomadic way of life.

Another critical factor in the predominance of transhumance is the seasonal disease risk posed by malaria in low-lying regions throughout the Mediterranean. Malaria, which is spread between humans by mosquitoes, thrives in regions with low elevation, high summer temperatures, and of course ample standing water to breed in. We've done a

three-part series on the history of malaria on Ottoman History Podcast that gives particular focus to the Ottoman context.

Faruk Tabak singles out malaria as one of the important factors encouraging a general increase in mountain settlements vis a vis lowland settlements in the Mediterranean during the early modern period. This claim is strengthened by the fact that yaylas were well-understood to be salubrious areas that offered special protection from disease. Evliya Çelebi's

Seyâhatnâme from the seventeenth-century, which among many things is a rich source for local information about the society, culture, and geography of the Ottoman world, comments on the importance of yaylas in protecting against illnesses including malaria (

sıtma) in regions such as Payas (modern-day Hatay province, Turkey) where locals had special beliefs about the power of the pasture (see

Seyahatname Vol.3 p.32).

A quick look at the elevation map of Southern Anatolia (Adana and Antalya regions in the migration maps above) on the right illustrates in very simple terms the importance of yaylas in protecting against malaria. The orange-yellowish areas of the map of more than 1 km in elevation are the principal destination regions for old summer migration. During the height of anti-malaria efforts in Turkey where DDT was aggressively deployed in regions such as the Çukurova plain surrounding Adana to kill mosquitoes, it was not deemed necessary to spray at elevations beyond 1200 meters or so. The map below from a Turkish government report on malaria control from 1949 shows the areas of malaria control in Turkey at that time. While the lack of malaria control in Eastern Turkey was likely due to an absence of adequate services and infrastructure, the patches of Central, Southern, and Western Anatolia that were without malaria control are all high elevation regions. In other words, moving to the yayla from May-October, the principal time of year when malaria can thrive in the Mediterranean (it is too cold for mosquitoes to proliferate in the winter) was a natural and indeed elegant solution for the endemic disease risk posed by malaria.

![]() |

| Source: Seyfettin Okan, Türkiye'de sıtma savaşı |

This point is further emphasized by the history of immigrant settlements in Anatolia. During the nineteenth century, Russian colonial policy in Crimea and the Caucasus sent hundreds of thousands of Muslims fleeing into the Ottoman Empire. The Ottoman state for its part attempted to settle these communities on "vacant" land, i.e. ones not possessed by a landholder but perhaps used for other purposes. For Tatar or Circassian immigrants, settlement in low-lying regions of Turkey's warmest provinces such as Adana spelled death; many of the settlements created in such regions no longer exist. However, villages founded at high elevations more similar to the Caucasian geography and better protected from disease stood a better chance. In

Episode 112 of Ottoman History Podcast, we told the story of one such village, Atlılar, where a Circassian community succeeded in establishing a permanent settlement on a yayla north of Mersin.

Outside of this impersonal geographically deterministic explanation for the phenomenon of transhumance and the importance of the yayla, I will note the pastoralist communities under discussion also comprised entire societies, not fully separate from broader Ottoman society politically and culturally but nonetheless exercising a large degree of autonomy and cultural uniqueness. These groups usually referred to English as tribes and in the Ottoman period defined variously using distinctions such as aşiret, oymak, cemaat, kabile, and others were able to maintain independence through a combination of mobility, self-reliance, and cooperation with the Ottoman state. Groups that today fall under ethnic and communal categories such as Yörük, Türkmen, Kürt, Alevi, Tahtacı, Bedevi, and others all took part in a pastoralist mode of production that shared among many things an admiration of the yayla and its culture. The yayla is associated with the symbolically significant spring months and springtime celebrations such as Hıdırellez that usually took place following migration to the mountains. Even for communities without fixed residences, the concept of home or sıla in Turkish could be associated with the safety of the summer pastures. Thus, the immense cultural significance of seasonal migration for the self-identification of these communities provided additional incentive for them to resist attempts at settlement and restriction of mobility by the state in addition to the threat it would pose to their flocks and livelihood.

Yet, alongside the cultural importance of the summer pasture as part of the deeply-rooted concept of home for transhumant communities must be considered the real ecological implications of settlement. Otherwise, resistance to state resettlement efforts whether around Adana during the 1870s or in Dersim during the 1930s appears merely as a reactionary rebellion against the rule of law of the modern state, i.e. a strugglesolely for autonomy. Forced settlement, which usually entailed a change in the relationship between pastoralist communities and the mountains, bore severe consequences in terms of the economic and physical health of those subject to such policies, and it is only within the context of these hardships that we can begin to understand the true legacy of what can be observed as a worldwide offensive by modern states against nomadic populations.

Settling Nomads

The factors that have led to the virtual disappearance of transhumance in regions of Anatolia where a significant percentage and in some cases majority of the population practiced some type of nomadic pastoralism as late as the nineteenth century are numerous, but state measures have played a critical role in this process. Ottoman governments had long maintained tense relations with mobile populations; they were difficult to control and tax but important military and economically. When possible, settlement was encouraged, though attempts to force settlement could be met with both passive and violent resistance. Well into the nineteenth century, the factors described above outweighed state pressure to settle in the balance of settlement and nomadism that emerged.

During the nineteenth century and particularly following the Crimean War, increased military power allowed the Tanzimat-era Ottoman state to force local populations in many parts of the empire to submit to taxation, conscriptions, and, in the case of nomads, settlement. Reşat Kasaba explains the shift towards forcing settlement in

A Moveable Empire. There were numerous reasons why settling nomads was seen as advantageous. Aside from the apparent ability to better control settled populations, promoting settled agriculture would allow the Ottoman economy to benefit from increased demand for cash crops such as cotton on the global market. Meanwhile issues regarding migration back and forth between pastures on increasingly defined borders posed problems in terms of diplomacy and security.

My broader dissertation research examines the impacts of a particular period of forced settlement in the Adana region initiated with the fırka-ı ıslahiye (reform army) in 1865. I have alluded to the ways in which this region was a center of transhumance above. Forced settlement in the Adana region was designed to secure the mountains by settling tribal communities into marginal areas of the Çukurova plain. Some groups agreed to settle without resistance while others fought the Ottoman army before being put down. Afterwards, the provincial government attempted to build houses and villages for the settled communities. However, due to the prevalence of malaria in these regions and other factors impeding a transition to settled life, these villages witnessed high mortality and rates of abandonment by those settled there, many of whom preferred to continue their migratory pattern when possible. The result of this process was thus a mixture of lingering transhumance coupled with the establishment of largely poor and disadvantaged rural communities that were on the margins of the emerging cotton economy.

While the case of Adana may display a particularly pronounced manifestation of the phenomena I associate here with forced settlement, this trend could be witnessed throughout Anatolia during the late Ottoman period and into the Republican era. Settlement occurred incrementally, driven by a combination of state pressure and economic incentive. Seasonal migration for health or comfort continued as a practice, but as former pastoralists became urban migrants and agricultural workers, the vitality of the yayla as an economic space waned, remaining largely as a nostalgic symbol of a prior mode of existence.

An Enduring Geography![]() |

A cable car conveys campers and

picnickers to summer plateaus

on Uludağ in Bursa, Summer 2009

Source: Chris Gratien |

Our world has undoubtedly witnessed a dramatic transformation with regard to the relationship between seasonal migration, pastoralism, and human settlement. Transhumance in the sense of exploitation of summer and winter pastures for grazing has come to be an extremely marginal practice when compared with pastoral farming and the increasingly industrialized production of animals and their products. With this change, the social space created by the summer pasture has also been modified, though not eliminated.

Given the discussion I have provided above, it is not surprising that in modern Turkey, the various products from yogurt and cheeses to carpets and comforters associated with traditional pastoral life in Anatolia have become romantically associated with a yayla kültürü or summer pasture culture. Mountain living is remembered with tremendous nostalgia, and many urban families maintain some link to the yayla in the form of summer homes or relatives in mountain towns and villages. Today, plateau regions are home to small towns linked to larger cities that offer temporary or permanent refuge from the burdens of urban life, and while these geographical regions are no longer significant as ground for grazing sheep and goats, they remain a fantastic places for grilling, picnicking, hiking and camping. The economies of these areas often thrive in part on the development of a robust yayla tourism industry in many parts of Anatolia.

![]() |

Planting trees with Fındıkpınarı Municipality

Source: Chris Gratien |

The symbolic significance of the yayla as a green ecological space associated with springtime, clean water, and fresh air also endures in the form of environmentally-oriented projects aimed at the preservation or revitalization of the summer pasture scene; however, these projects occur within a radically different cultural and socioeconomic context than that which originally imbued them with their special meaning. For example, in Spring of 2013, I participated in a trip to the town of Fındıkpınarı near Mersin, Turkey where the municipality had arranged for a group of students to participate in the reforestation of the yayla by planting trees on the hillsides of a plateau region. Of course, the reforestation of these areas, which were well-deforested even before the Ottoman period, can only be imaged in a time when these spaces are no longer considered vital for the pastoralist economy as sources of grass for livestock. Only with changing times and significant intervention by the state has the yayla become imagined as a place where pristine nature might be nurtured and preserved.

Yet, this does not mean that the time for summer pastures has altogether passed. One can still spot small flocks of sheep throughout the most sparsely populated and mountainous ares of Turkey, and in keeping with the nomad's tendency to use space extensively (i.e. to expand activities to fill available space), today's herders and shepherds are also ready to capitalize on new economic opportunities for grazing. For example, the spread of trucks and vans throughout the Middle East has allow for a whole new type in nomadism wherein the shepherd move the flock by motor vehicle. The below chart from an

article by Dawn Chatty on the pastoral family and the truck in Lebanon details the daily activities of various members of a Bedouin family living near the Syrian border during the 1960s.

![]() |

| Source: Dawn Chatty, "The pastoral family and the truck" in When Nomads Settle (1980) |

Moreover, when the conditions that eliminated transhumance are no longer present, a resurgence is possible. In modern Armenia, for example, economic and demographic decline since the fall of the Soviet Union and the Armenian-Azerbaijani War has left the countryside abandoned, particularly in parts of the country that were formerly home to Muslim inhabitants. The wide availability of land has created not just new potential for pastoralism but critical need to explain the country's vacant pastures, leading even to talk of renting the pastures to Iranian sheep according to

an article by James Brooke entitled "The Geopolitics of Sheep in an Armenian Region."![]() |

Tent of cattle herders near Kari Lich, Armenia

Summer 2010

Source: Chris Gratien |

During the summer of 2010, I made a short hike that began at Lake Kari, a highland lake on the slopes of Mount Aragats in Armenia located at over 3,000 km above sea level. Even on the sunniest summer days, the air is cold on the highland plateau between Lake Kari and the town of Byurakan below, making it a prototypical summer pasture. There, one encounters small communities of Kurdish-speaking Yezdis (or Yazidis), who by and large remained in Armenia following the Nagorno-Karabakh war unlike their Muslim Kurdish counterparts. These communities have traditionally practiced pastoralism and thus have enjoyed some prosperity as of late due to good access to pastures in Armenia. However, a more surprising presence on the plateau is that of Armenian families from Yerevan who take up residence in large tents and tend to cattle on the yayla. I spoke with a young man who explained that while he was from the city, coming up to the pasture during the summer to raise animals offered his family a low-cost means of earning some extra money. Admittedly, he was not nearly as enthusiastic about being on the yayla as I was, but nonetheless, the combination of opportunity and incentive that brought his family to the summer pasture is a testament to the ways in which transhumance remains as it always has a viable extension of and indeed complement to settled life.

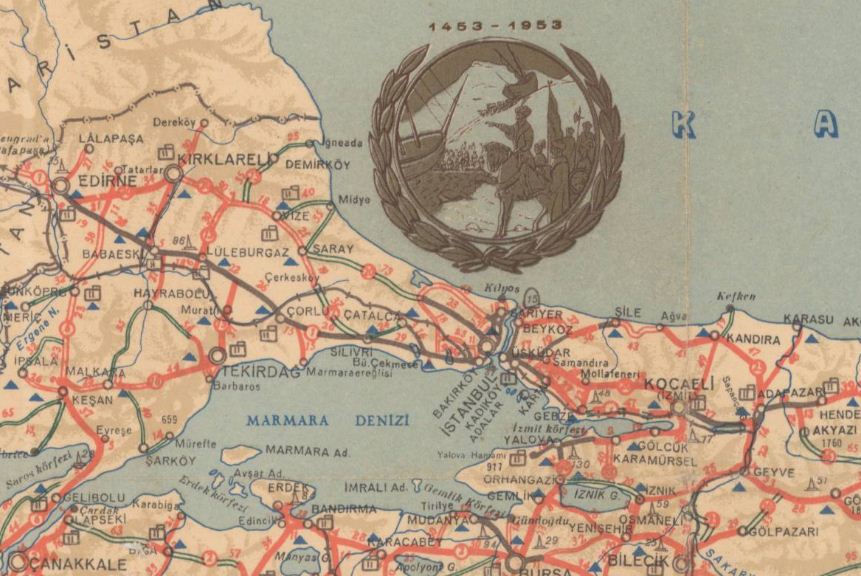

Anyways, as an op-ed in in (tomorrow's) Today's Zaman and a photo collection from OHP suggest, the 500th anniversary of the Fetih in 1953 served as an opportunity for Turkey's leaders to present Fatih as an enlightened, tolerant secular, Western-Oriented leader. In short, a good Kemalist five centuries ahead of his time. The image above, for example, is the annual highway map from the Karayollari Mudurlugu, invoking Fatih as a symbol of engineering prowess in order to tout the Democrat Party's road-building program. At the same time, as the cartoons in our photo album show, the opposition used this same interpretation of Fatih to criticize the government for not doing more to improve Istanbul's infrastructure.

Anyways, as an op-ed in in (tomorrow's) Today's Zaman and a photo collection from OHP suggest, the 500th anniversary of the Fetih in 1953 served as an opportunity for Turkey's leaders to present Fatih as an enlightened, tolerant secular, Western-Oriented leader. In short, a good Kemalist five centuries ahead of his time. The image above, for example, is the annual highway map from the Karayollari Mudurlugu, invoking Fatih as a symbol of engineering prowess in order to tout the Democrat Party's road-building program. At the same time, as the cartoons in our photo album show, the opposition used this same interpretation of Fatih to criticize the government for not doing more to improve Istanbul's infrastructure.