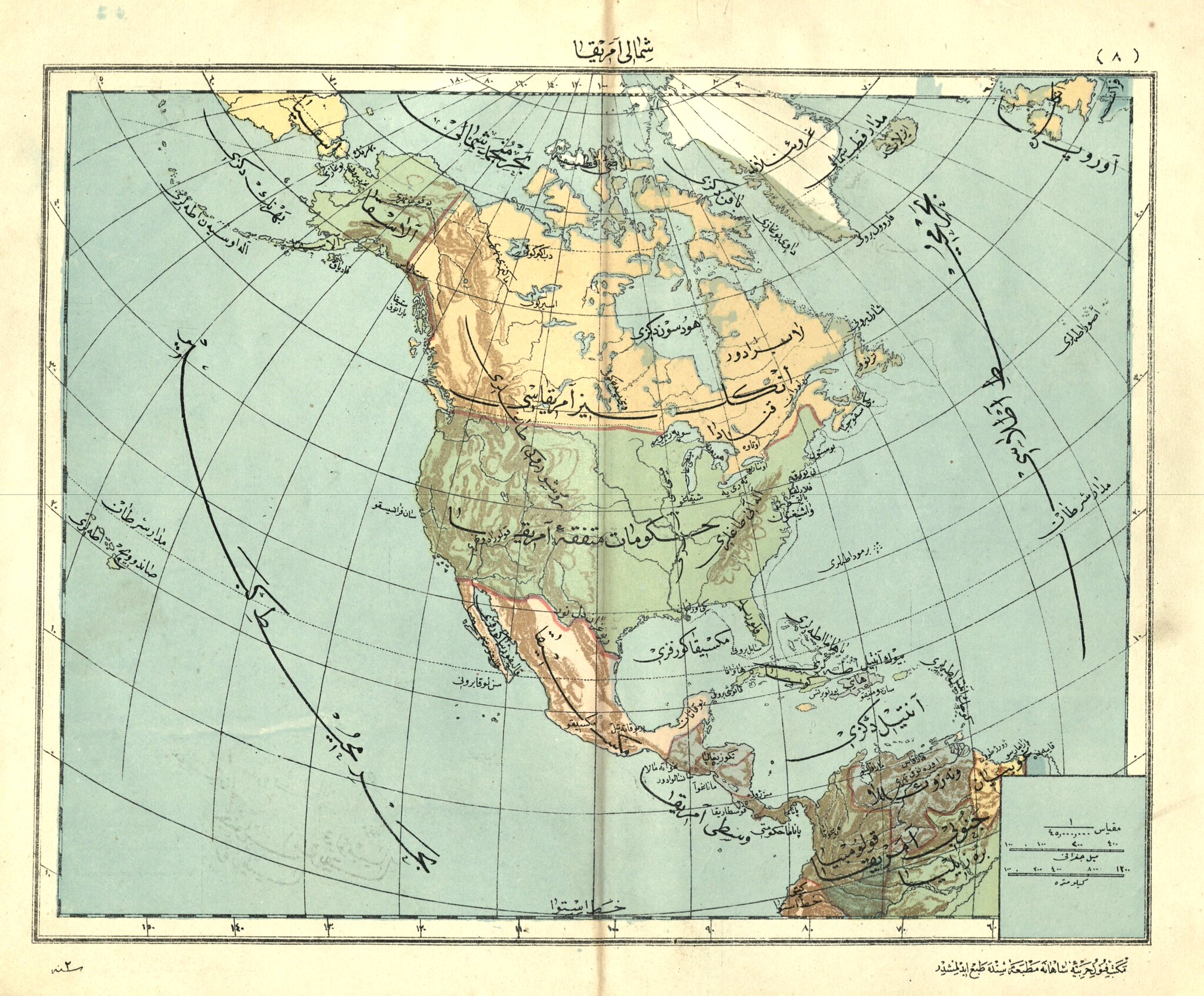

Last week our blog had its 100,000th visitor, an exciting milestone a little less than a year after we began. In honor of the occasion we have a blogger-generated map showing were you, our readers, are from. Not surprisingly, Turkey had the most, with America a close second and regular traffic from Canada, Western Europe and China as well. We also wanted to revisit some of our most popular maps. First and foremost is "Still Seeing Red", whose popularity was due to its supposedly revealing that Erdogan's Canal Istanbul project was actually an American plot [Obviously America's real scheme involves the Bosphorus Funicular]. Also popular have been an Ottoman maps of Beijing and North America, Zach Foster's excellent essay on mapping Palestine, some beautiful maps of trains and trams, and our home-made map of the changing border between East and West. And finally, a few maps that weren't that popular, but are still some of my favorites: this Goat map, Naci Dilekli's hand-drawn Dervish Map (or Sema Schema) and this incredible guide to oil wrestling by world champion Adali Halil.

↧

Article 13

↧

An Ottoman Map of Nazi Europe

Nick Danforth, Georgetown University

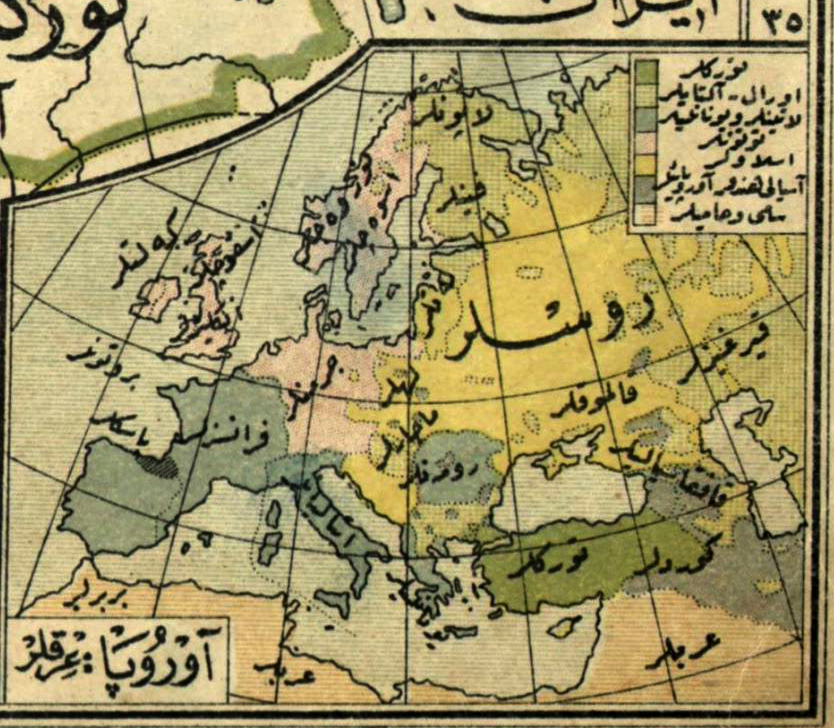

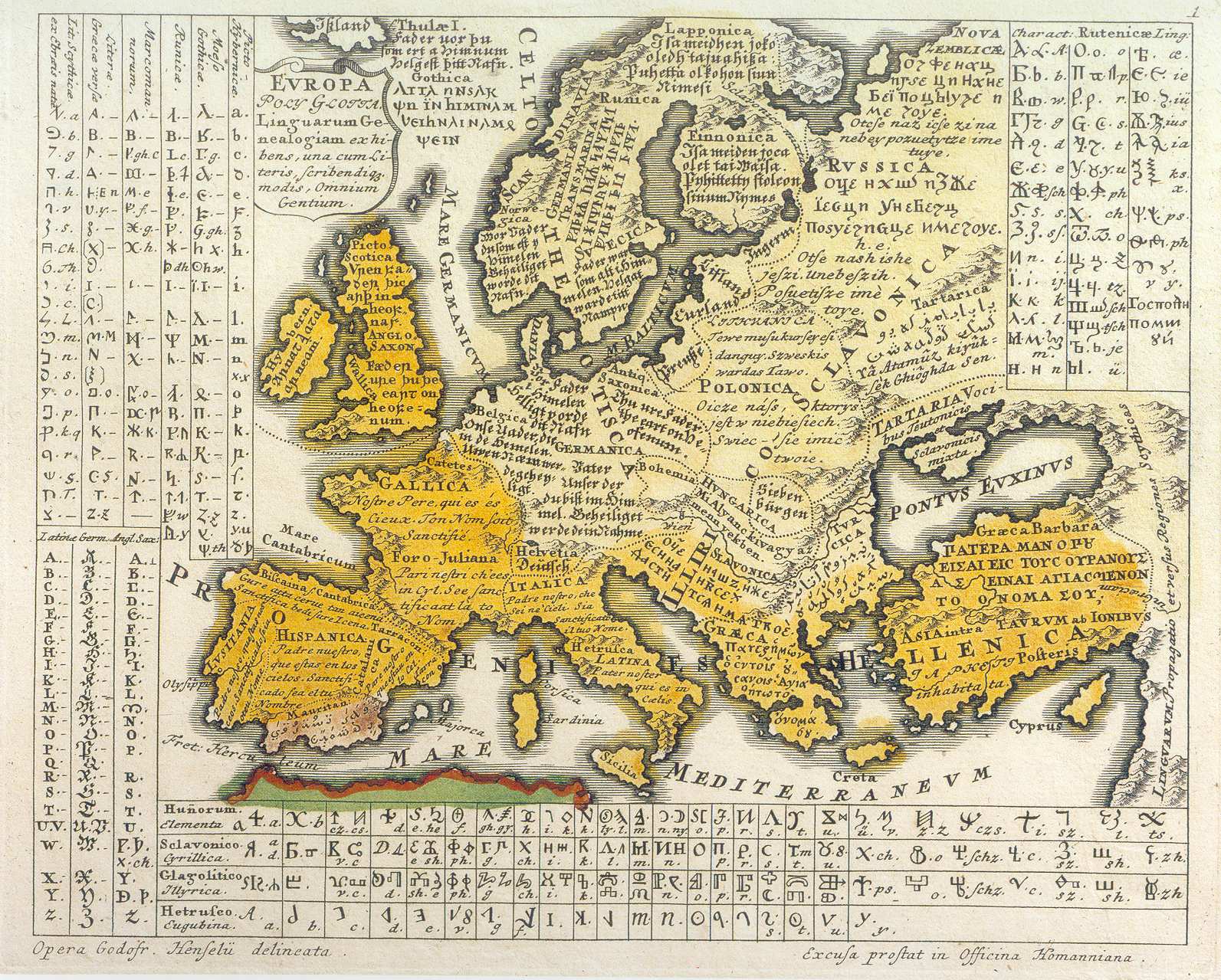

At first glance this is just another nice old map that some kid ruined with a colored pencil. A second glance, though reveals an incredible anachronism. The pink cross-hatched region corresponds perfectly to the extent of German conquests during the opening years of World War Two (maybe late 1940?). Before the advent of cheaply produced maps or the internet, people had to make their maps last, and would often update them by hand to reflect political changes. A number of Turkish maps show up with Hatay drawn in by hand after 1939, alongside those with a line sketched in between East and West Germany or offending place names vigorously crossed out. This map also serves as another reminder that Ottoman script remained widely used and understood through most of the 20th century. Through the 70s it is easy to find letters, shopping lists and margin notes jotted down in Ottoman by members of a generation that learned it first at an impressionable age. The best anecdote on the subject, quite possibly apocryphal, involves a late-night meeting during the 30s where one of Ataturk's companions was diligently taking notes in the Ottoman script. Hearing someone at the door, Ataturk turned to him and said "Quick, put that away. Ismet Pasha's coming." In any case, not knowing anything about the owner of this map, it's nice to imagine it was a precocious kid eagerly following radio news bulletins from the floor of his or her parents' living room, rather than a grown up fascist sympathizer.

Also as a follow-up to last week's discussion of ethnographic maps, here's a little snippet from the bottom corner labelled "Races of Europe." It includes the Celts, Scots and English in Britain, Arabs and Berbers in North Africa, Kyrgyz (a term formerly used for Khazaks), Kalmuks and Caucasians in Southern Russia and as best I can make out "Lapunlar" in Lapland. The Bulgarians appear as Ural-Altaylar and the Kurds appear in southeastern Anatolia. Like many maps from the late Ottoman and Early Republican period, this was produced by the well known British mapmakers George Phillip & Sons.

At first glance this is just another nice old map that some kid ruined with a colored pencil. A second glance, though reveals an incredible anachronism. The pink cross-hatched region corresponds perfectly to the extent of German conquests during the opening years of World War Two (maybe late 1940?). Before the advent of cheaply produced maps or the internet, people had to make their maps last, and would often update them by hand to reflect political changes. A number of Turkish maps show up with Hatay drawn in by hand after 1939, alongside those with a line sketched in between East and West Germany or offending place names vigorously crossed out. This map also serves as another reminder that Ottoman script remained widely used and understood through most of the 20th century. Through the 70s it is easy to find letters, shopping lists and margin notes jotted down in Ottoman by members of a generation that learned it first at an impressionable age. The best anecdote on the subject, quite possibly apocryphal, involves a late-night meeting during the 30s where one of Ataturk's companions was diligently taking notes in the Ottoman script. Hearing someone at the door, Ataturk turned to him and said "Quick, put that away. Ismet Pasha's coming." In any case, not knowing anything about the owner of this map, it's nice to imagine it was a precocious kid eagerly following radio news bulletins from the floor of his or her parents' living room, rather than a grown up fascist sympathizer.

Also as a follow-up to last week's discussion of ethnographic maps, here's a little snippet from the bottom corner labelled "Races of Europe." It includes the Celts, Scots and English in Britain, Arabs and Berbers in North Africa, Kyrgyz (a term formerly used for Khazaks), Kalmuks and Caucasians in Southern Russia and as best I can make out "Lapunlar" in Lapland. The Bulgarians appear as Ural-Altaylar and the Kurds appear in southeastern Anatolia. Like many maps from the late Ottoman and Early Republican period, this was produced by the well known British mapmakers George Phillip & Sons.

↧

↧

The Hippie Trail

Nick Danforth, Georgetown University

![]() "This is not the end, Just the beginning"

"This is not the end, Just the beginning"

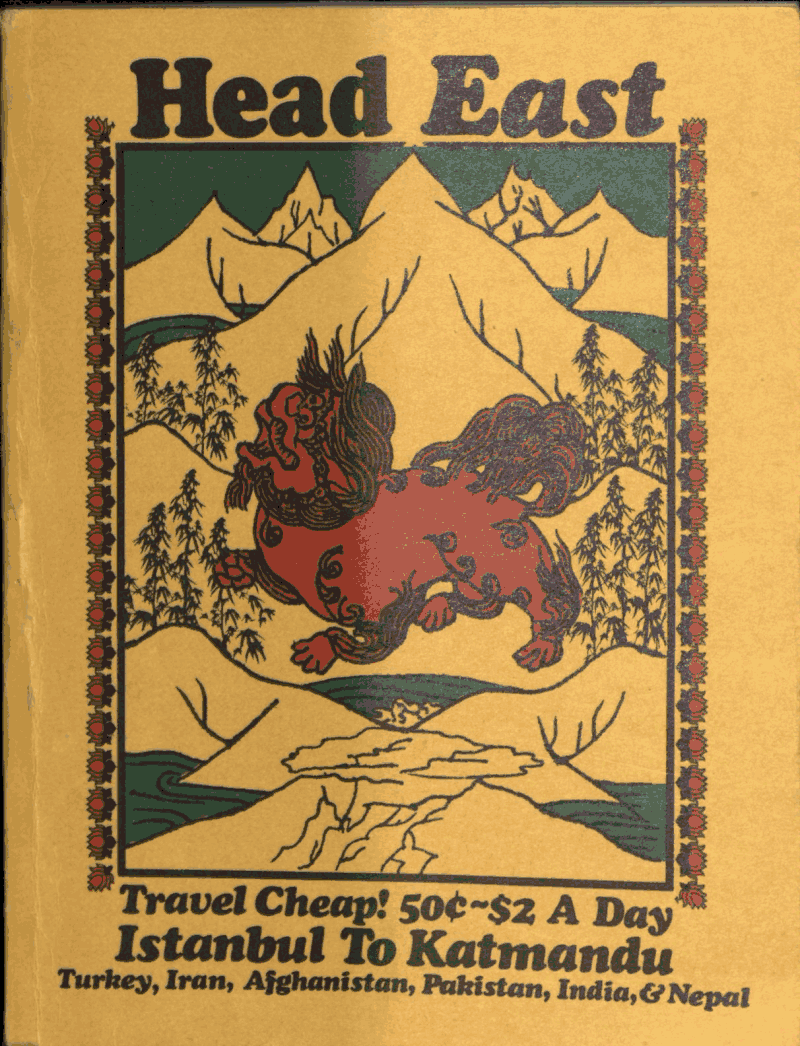

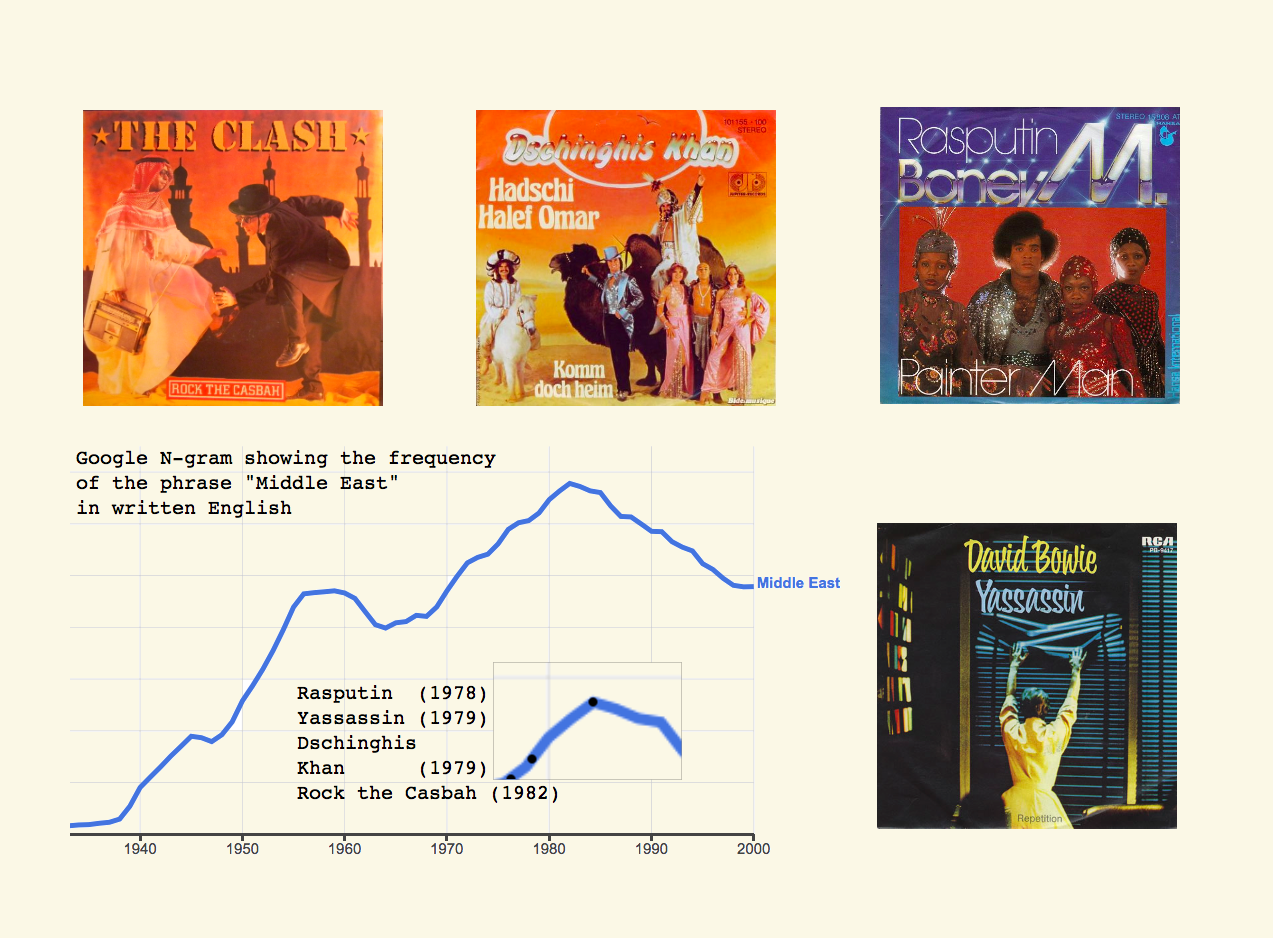

If there's one aspect of Turkey that we don't talk about much these days, its the country's former importance as the starting point of the Hippie Trail. Among other things, hippies get an excellent entry in Reşat Ekrem Koçu's Istanbul Encyclopedia, complete with a drawing, a whimsical poem, and a bit making fun of religious men who taunted the hippies in Sultanahmet by day, then returned to try to pick up hippie women by night. It's proved surprisingly hard to find good maps of the hippie trail, which I'm sure must have existed. There's this way too computer-designed looking map from Richard Gregory's The Hippie Trail 1974, as well as the inevitably competent wikipedia map. There is also this old bus route and another bus-themed graphic from an article about the Cruise of the Indiaman. The best thing available online is probably this map (detail), from this guy, who also includes some othergreat pictures from his 1978 trip. In any case if any of our readers have maps lying around they should send in a copy. In the meantime, we're publishing some excerpts covering the Middle Eastern part of the trail from this 1973 travel guide. Many of us, I suspect, felt a certain disappointment on discovering after our first trip to the region that our grown up relatives already had considerably better stories about traveling there than we did. An aunt, for example, shared a train compartment on her first trip to Istanbul with a few Germans. When they arrived in the morning the guy who had been sleeping in the hammock by the window was gone. A few days later he showed up, saying someone had rolled him out of the window when the trains slowed to go through a town, taken his money and left him in a field by the highway. Now you can take the trip on a tour bus with a bunch of Australians.

More seriously, though, for all of our discussions about the legacy of 19th century orientalism in shaping Western views of the Middle East, it seems worth considering that a particular view of the region that emerged in the 60s and 70s and is reflected quite clearly in this guidebook also influenced the way quite of few people now in positions of power first learned to see the region. There's obviously a good deal of variety in how hippie travelers saw the regions they passed through, but it seems fair to say that in a lot of cases they simply took long standing stereotypes about the region and reversed the value judgements. As the guide's introduction suggests, the East's lack of constraint, rationality and plastic materialism makes the Easterner more in touch with reality and gives him or her a better perspective on "life, time, people drugs and living in general."

Anyways, read the guide after the break and set out for Kandahar:

"This is not the end, Just the beginning"

"This is not the end, Just the beginning"If there's one aspect of Turkey that we don't talk about much these days, its the country's former importance as the starting point of the Hippie Trail. Among other things, hippies get an excellent entry in Reşat Ekrem Koçu's Istanbul Encyclopedia, complete with a drawing, a whimsical poem, and a bit making fun of religious men who taunted the hippies in Sultanahmet by day, then returned to try to pick up hippie women by night. It's proved surprisingly hard to find good maps of the hippie trail, which I'm sure must have existed. There's this way too computer-designed looking map from Richard Gregory's The Hippie Trail 1974, as well as the inevitably competent wikipedia map. There is also this old bus route and another bus-themed graphic from an article about the Cruise of the Indiaman. The best thing available online is probably this map (detail), from this guy, who also includes some othergreat pictures from his 1978 trip. In any case if any of our readers have maps lying around they should send in a copy. In the meantime, we're publishing some excerpts covering the Middle Eastern part of the trail from this 1973 travel guide. Many of us, I suspect, felt a certain disappointment on discovering after our first trip to the region that our grown up relatives already had considerably better stories about traveling there than we did. An aunt, for example, shared a train compartment on her first trip to Istanbul with a few Germans. When they arrived in the morning the guy who had been sleeping in the hammock by the window was gone. A few days later he showed up, saying someone had rolled him out of the window when the trains slowed to go through a town, taken his money and left him in a field by the highway. Now you can take the trip on a tour bus with a bunch of Australians.

More seriously, though, for all of our discussions about the legacy of 19th century orientalism in shaping Western views of the Middle East, it seems worth considering that a particular view of the region that emerged in the 60s and 70s and is reflected quite clearly in this guidebook also influenced the way quite of few people now in positions of power first learned to see the region. There's obviously a good deal of variety in how hippie travelers saw the regions they passed through, but it seems fair to say that in a lot of cases they simply took long standing stereotypes about the region and reversed the value judgements. As the guide's introduction suggests, the East's lack of constraint, rationality and plastic materialism makes the Easterner more in touch with reality and gives him or her a better perspective on "life, time, people drugs and living in general."

Anyways, read the guide after the break and set out for Kandahar:

↧

Paradise Found

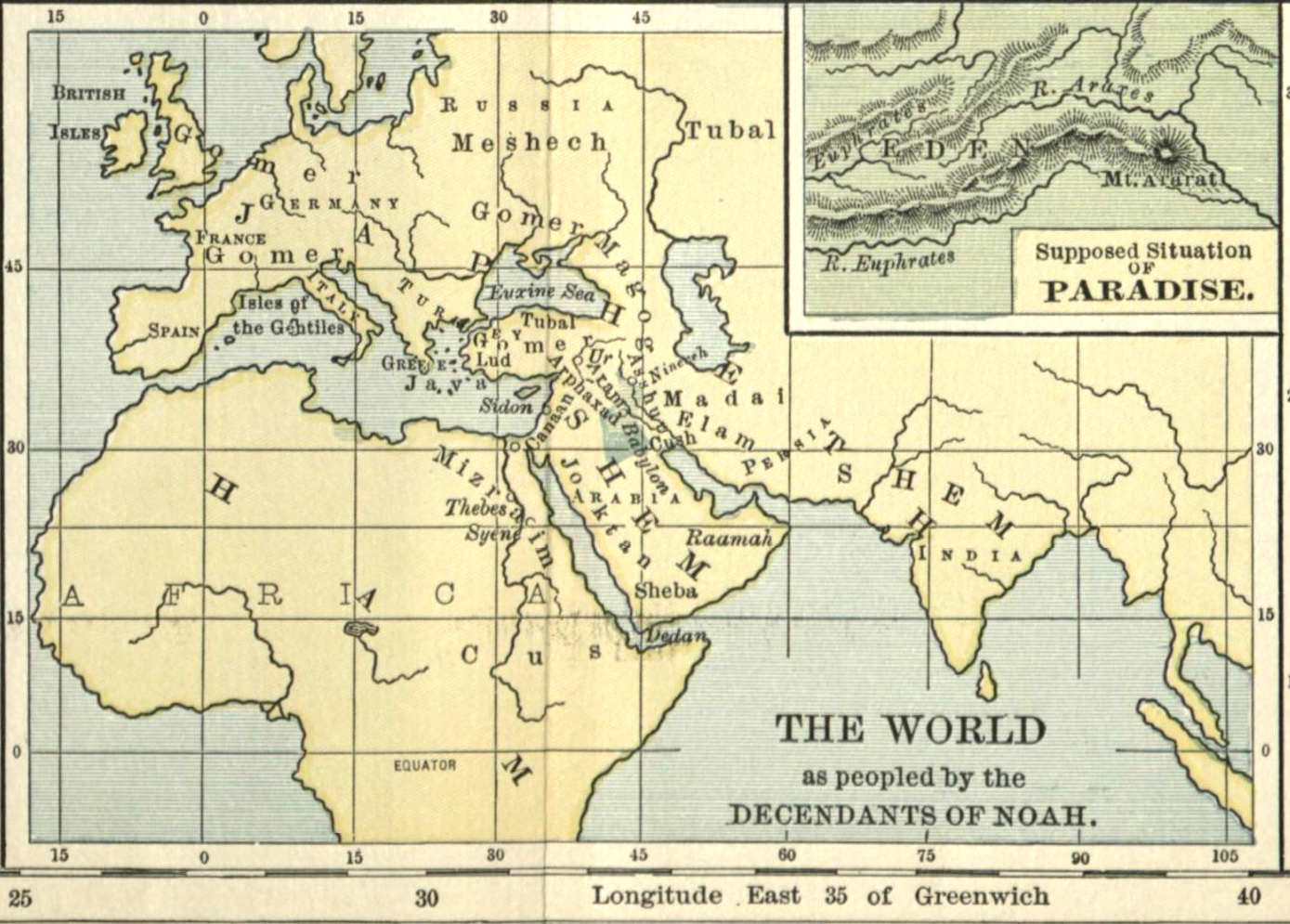

Based on this description, at least, Eastern Anatolia, near the origins of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, seems about as good a guess as any. I don't know much about the larger map, showing the world as peopled by the descendants of Noah. The children of Japhet are in Europe, the children of Ham, or Hamites, are in Africa, and the children of Shem, or Semites, are in the Middle East. The people of Magog are still spread across the Caucasus, before legend has it that Alexander the Great built an iron wall in order to safely contain them north of the mountain range. The miniature left, showing the building of the wall, comes from a 16th century illustration of the Falname."A river flowed out of Eden to water the garden, and there it divided and became four rivers. The name of the first is the Pishon. It is the one that flowed around the whole land of Havilah, where there is gold. And the gold of that land is good; bdellium and onyx stone are there. The name of the second river is the Gihon. It is the one that flowed around the whole land of Cush. And the name of the third river is the Tigris, which flows east of Assyria. And the fourth river is the Euphrates."

↧

America's Allies and Enemies in the Middle East: An Afternoon Map Movie

US policymakers and internet map lovers share a certain enthusiasm for radically simplified visions of the world. With this in mind I put together the following map showing how America's relationship with the various countries of the Middle East evolved over the past 75 years. The color scheme should be pretty self-explanatory. I tried as best as possible to reduce every complex bilateral relationship into the "with us or against us" dichotomy prevalent during the Cold War and the War on Terror, but in some cases (particularly between these eras in the 90s) it was necessary to introduce the ambiguous purple. There were, of course, plenty of arbitrary decisions that had to be made (when, for example did Pakistan go from friend to - thanks Foreign Policy - "frenemy") and I made them arbitrarily. The same goes for the symbols, denoting changes that occurred on account of invasions (the tank), coups (the gun), treaties or diplomatic decisions (the pen), elections (the check), other peaceful transfers of power (the weird baton thingy) or popular uprisings (the protestor). In any case, here is the map. You can watch it as a GIF, a format which nicely captures the inevitable unfolding of events faster than we can hope to fully observe or grasp them, or as a Youtube Video, corresponding to the historian's fantasy of being able to pause, study and replay the progression of time.

* If I'd had more time and realized how many people were going to see this, I would have added a little more geographic nuance by breaking the map down to incorporate Iraqi Kurdistan, Nagorno-Karabagh, Abkhazia and South Ossetia. It's interesting, actually, to see how few de jure border changes there have been in the region over the past 75 years.

** Excellent suggestions keep coming in for music to set this to, including some kind of frantic ragtime, a heavy metal anthem or something more pointed like "We Didn't Start the Fire" or Shaggy's "It Wasn't Me."

↧

↧

Cheese Map

Several years ago I got a ride from a truck driver who worked for an Edirne-based cheese factory. He told me that Turkey had over 330 kinds of cheese. At the time I was naive enough to think this must be an absurd exaggeration, or at least an incredibly optimistic way of counting minor variations on beyaz peynir. Now I know better, thanks in part to Artun Ünsal's excellent book Süt Uyuyunca [While Milk Sleeps] from which this map is taken.

↧

Burn the Maps and Run

Though the accidentally obscene English language tee-shirt has become something of a cliche in tourist photos and Radikal articles, I feel like the brilliant nonsense of so many of the Istanbul's shirts is far too often overlooked. With sayings like "Sexy or Sexy: That is the Question,""I can fly with my secret wings,""Squirrel Beatbox," "Shut Up Owl," or maybe just a paragraph from the wikipedia article on the Bering Sea, these shirts tread the line between sense and nonsense in a manner that is truly sublime. Since we've already taken a break from real history with today's cheese map, here is one of our favorites, courtesy of the blog Nonsense Shirts.

|

| http://nonsenseshirt.tumblr.com/ May 22, 2013 |

↧

Know Your Neo-Ottomanisms

Nick Danforth, Georgetown University

Today we return to a theme we've written about with what some might now say is gratuitous regularity: the politics of Ottoman history in contemporary Turkey. This article was originally scheduled for publication elsewhere when at the last minute the editors decided it was unredeemably "polemical and hyperbolic." Which, of course, made me think it just might work as a blog post:

Today we return to a theme we've written about with what some might now say is gratuitous regularity: the politics of Ottoman history in contemporary Turkey. This article was originally scheduled for publication elsewhere when at the last minute the editors decided it was unredeemably "polemical and hyperbolic." Which, of course, made me think it just might work as a blog post:

At a time when almost every discussion of Turkish politics involves a reference to Neo-Ottomanism, it’s a shame no one can quite agree on what exactly the phrase means. As a result, after years of describing Prime Minister Erdogan’s friendship with Bashar Assad as evidence of his neo-Ottoman tendencies, critics could seamlessly transition into describing his efforts to topple the Assad regime as neo-Ottoman too. Meanwhile, EU-inspired efforts to use Ottoman tolerance as a political model for a post-national world co-exist with nationalist rhetoric in the Greek and Armenian diasporas that uses “neo-Ottoman” as a term of abuse almost on par with “neo-Nazi.”

Much of this confusion stems from the fact that for over half a century, adherents of widely divergent ideologies have been celebrating rival interpretations of the Ottoman past in order to promote their own particular agendas. Discussions today often presume that the politics of Ottoman history have always been a battleground between pro-Ottoman Islamicists and anti-empire secularists, in which the Islamists have only recently gained the upper hand by taking control of the state and its history-writing apparatus. The truth is that from at least the late 1930s onwards—no more than a decade after the formation of the Turkish Republic—almost everyone in Turkey has been eager to incorporate the heroic achievements of the Ottoman golden age into their preferred national narrative. The debate, in fact, has always been over whose reading of the Ottoman past should be celebrated. Where some have seen a pious yet “tolerant” Hanafi Islamic Empire, others have seen a secularist Turkish nation-state. Still others have rushed to celebrate a multi-cultural, pre-national paradise to be redeemed under the banner of “liberal democracy.”

On one ideological extreme are those Islamists who seek to extract from the Ottoman past an Islamic identity capable of supplanting Turkish nationalism entirely. Though this is certainly a minority position in contemporary Turkey, it has gained considerable attention because it so perfectly inverts the supposed Kemalist view of the Ottoman past. That is, in the very early years of the Republic, Mustafa Kemal made the Ottomans a foil for the secular nation-state he sought to build by denouncing them as fanatically religious foreign usurpers who repressed their people’s Turkishness. As analyzed by scholars such as Alev Çınar, contemporary Islamist discourse seek to reverse this Kemalist project by replacing Turkishness with Islam and, in Çınar’s example, celebrating the conquest of Istanbul in 1453 instead of the foundation of the Republic in 1923. Though I would argue the vast majority of Turkish Islamists are devoted nationalists committed to some form of Turkish-Islamic synthesis, anti-nationalist Islamism has made sporadic appearances in mainstream discourse at least since the 1930s. More recently, though, shared Islamic values have been invoked in an attempt to transcend divisions created by official nationalist discourse. In 2008, for example, Erdogan famously said, in support of his Kurdish outreach initiative, that something was terribly wrong when Turkish and Kurdish mothers both recited the Fatiha over the caskets of their fallen sons.

The focus on Mustafa Kemal’s anti-Ottomanism has led observers to ignore the Kemalist appropriation of the Ottoman past that occurred in the late 1930s, which subsequently dominated popular and official thinking. Culminating in the massive celebration of the five-hundredth anniversary of Istanbul’s conquest in 1953, Turkish nationalists realized that rather than denouncing the Ottoman past as religious and non-Turkish, they could redefine it as secular and Turkish, then celebrate it.[1] Articulating what Buşra Ersanlı has called a “theory of fatal decline,” Kemalist scholars like Afet Inan have argued that the Ottoman Empire had been strong and successful in its Golden Age because it stayed immune from foreign and religious influence until, in the seventeenth century, fanaticism took hold of the Empire, its Turkish element became diluted, and decline set in.[2] Celebrating Fatih Sultan Mehmet II in 1953, journalists and politicians fell over themselves to describe him as a “secular,” “western-oriented,” and “revolutionary” Turkish leader whose conquest of Istanbul helped bring the Middle Ages to a close, ushering in a new era and even the Renaissance.[3]In their words, Fatih had been a pioneer of human rights and religious tolerance, so much so that they even suggested his ideology was embodied in the UN and NATO charters.[4]Like Ataturk, this “Great Turk” had rescued Istanbul from foreign hands and given it as an eternal gift to the Turkish nation.[5].

Secular Turkish Ottoman heroes have also been a staple of adventure novels, romances, and action movies over the last half-century. These fictional works amplified the prevalent themes in academic history, offering a similar ideology in starker, less nuanced terms. From Fazil Ferdiun Tulbentci’s ruddy, wine-quaffing, Turkish mariner Heyrettin Barbarosa, who first appeared in the pages of the CHP party paper Ulus in 1948, to Cuneyt Arkin’s Kara Murat in the 1970s, popular “Ottoman” heroes defended good Muslim Turks from their perfidious Christian foes while remaining perfectly secular in their own behavior. The more recent controversy over the soap opera Muhtesem Yuzyil—which Erdogan attacked for suggesting that Suleiman the Magnificent spent more time in the bedroom than on a horse—echoed debates over the first silver-screen sultans of the 1950s, which were repeatedly attacked on similar grounds.

Today, as many Islamists have sought to claim the Ottomans as pious Muslim rulers, there are a growing number of secularists who seek to articulate their politics in resolutely anti-Ottoman terms. Far more common, though, even among the AKP’s most vociferous critics, is a desire to defend the secular Ottoman discourse against Islamist appropriation. With prominent historians weighing in on debates over whether the Ottomans kissed and controversies over explicit Ottoman poetry, Turks of all political persuasions generally accept the Ottomans’ centrality to contemporary Turkish identity, then debate the Ottomans’ identity the way Americans debate the religiosity of the Founding Fathers with an eye toward the present. When Islamists turned out to celebrate the death of Ertegrul Osman in 2009, for example, Soner Çağaptay declared, “I want my Caliph back,” referring to the “Scotch-drinking, classical music-listening” heir to the Ottoman throne who had believed in the Turkish Republic at the expense of his family itself.

Today, though, there is no escaping the fact that the Ottoman past has come under the control of political Islam in Turkey. As authors such as Sam Kaplan and Etienne Copeaux have demonstrated, this process began with the articulation of a Turkish-Islamic Synthesis by right-wing intellectuals in the 1960s and 1970s. The Synthesis—famously summarized as “the best Turk is a Muslim, the best Muslim is a Turk”—gained force in the 1980s when it was promoted by the Turkish military as an antidote to “godless” communism. The rise of political Islam over the past two decades has made a synthesis-inspired reading of Ottoman history the central one in Turkish politics. Thus no one was surprised when the recent film Conquest 1453 began with a quote from the Prophet and included, alongside a love story and a parable about fatherhood, lengthy footage of Fatih’s men praying before capturing Istanbul.

It is worth noting that, to the extent that Ataturk’s vision of Turkish nationalism always included some element of shared Islamic identity at its core, even secular articulations of the Ottoman past made use of Islamic symbols. For example, a young Nazim Hikmet, in an early poem written before he became a communist, used Fatih’s transformation of Hagia Sophia into a mosque as a symbol of Turkish national pride. What stands out about the current Islamist Ottomania is both the emphasis on the piety of Golden Age sultans like Fatih and Suleiman and but also the attempt to reclaim later sultans like Abdulhamid II, who were disparaged by even the most pro-Ottoman Kemalists.

One of the most striking differences between the secular pro-Ottoman discourse and its Islamist counterpart lies in the way each uses the idea of “Ottoman tolerance.” Nationalists insist that tolerance is an innate Turkish virtue practiced by the Ottomans as Turks, while Islamists emphasize that the Ottomans were tolerant in accordance with the enlightened precepts of their Islamic faith. Adherents of both discourses have been all too happy to take the rhetoric of Ottoman tolerance to chauvinistic extremes, drawing pointed contrasts between the Ottoman Empire’s enlightened behavior and the barbaric intolerance of the Ottomans’ non-Turkish, non-Islamic enemies. Even in more moderate form, both of these discourses remain distinct from the truly liberal vision of pre-national Ottoman multiculturalism that has been advanced by many academics, artists, and progressive thinkers.

In this more sincere form, the discourse of Ottoman multiculturalism combines an academic effort to overcome the limitations of nationalist history with a political project seeking to overcome the limits of national borders. Historians have effectively dismantled an outdated—though still popular—literature that projected twentieth-century national rivalries back into the Ottoman past. In the political realm, governments and international institutions have selectively appropriated this history for their own ends while also funding its production. In the process, an academic literature focusing on syncretism, malleable identities, and cross-cultural flows has been transformed into a sometimes romanticized vision of an Ottoman Empire where co-existence rather than conflict was the norm.

Among other things, the discourse of Ottoman multiculturalism offers an intriguing look at the relationship between academic and popular historiography. For example, if anyone read the entirety of Caroline Finkel’s Osman Dream they would—I assume—get a nuanced picture of Ottoman policy toward minorities at various points in its long history. But the point is I haven’t read the whole thing, nor have a lot of graduate students I know studying Ottoman history. Most people will put down the book with Finkel’s introductory discussion of Ottoman tolerance on page twelve defining their view of the Empire’s history. And of course the number of people who even bought Osman’s Dream in the first place is dwarfed by the number who bought Birds Without Wings, a novel that paints the Ottoman period as an almost Edenic era—the setting is a town called Eski Bahce or Old Garden—defined by syncretism an inter-communal romance. [

While it is no longer controversial to suggest that during the twentieth century, nation-states promoted the writing of national history to advance their interests, historians have been more hesitant to accept the fact that, in the twenty-first century, international institutions have had equally pragmatic reasons for advancing a new vision of trans-national history. The EU, for example, which has a clear interest in transcending regional borders and the nationalist rivalries behind them, has played an important role in funding the conferences, books, museums, and universities that have promoted the idea of Ottoman multiculturalism. Turkish businessmen, for their part, are well aware that it is easier for their expanding companies to sell biscuits in former Ottoman lands with rhetoric that stresses harmony rather than hostility.

Once observers move beyond a reflexive association between Ottoman nostalgia and political Islam, they will be better able to understand how the Ottoman past, like all history, is an arena for symbolic competition between all of the obvious ideologies—nationalism, religion and liberalism—vying for control of Turkey's future.

[1] A number of images of these celebrations are available courtesy of the Ottoman History Podcast.

[2] Afet Inan, ‘Türk-Osmanlı Tarihinin Karakteristik Noktalarına bir Bakış,’ Belletin, Volume 1, 1937.

[3] For an overview of the ceremonies, see Ferdi Öner, “Fethin 500 uncu yıldönümü Tören ve Şenlikleri başladı.” Cumhurriyet, 30 May 1953; or “Fatih ve Topkapi’daki torende yüzbinlerce Istanbullu bulundu,” Vatan, 30 May 1953. For some particularly striking examples of typical Conquest Day rhetoric, see Sami Nafiz Tanus, ‘Sanatkar Fatih,’ Cumhuriyet, 31 May 1953; Hasan Ali Yücel, “Fethin Önemi,” Cumhuriyet, 29 May 1953; or Atac, “Yeni,” Ulus, 31 May 1953.

[4] See Morris Kaplan, “Turks Here Will Sip ‘Lion’s Milk’ To Mark Victory of 500 Years Ago,” New York Times, 29 May 1953; “Istanbul Fatih’i kucakliyordu,” Istanbul Ekspres, 29 May1953; Ecvet Guresin, “Tolerans Bayrami,” Vatan, 7 June, 1953; or the Fetih Day speech by Istanbul’s Mayor Fahreddin Kerim Gökay widely reported on 30 May.

[5]“Ankara’da Dun Yapilan Torenler.” Ulus, 30 May, 1953; “Times’in Fatih ve Atatürk yazisi vesilesile,” Cumhuriyet, 10 June, 1953.

↧

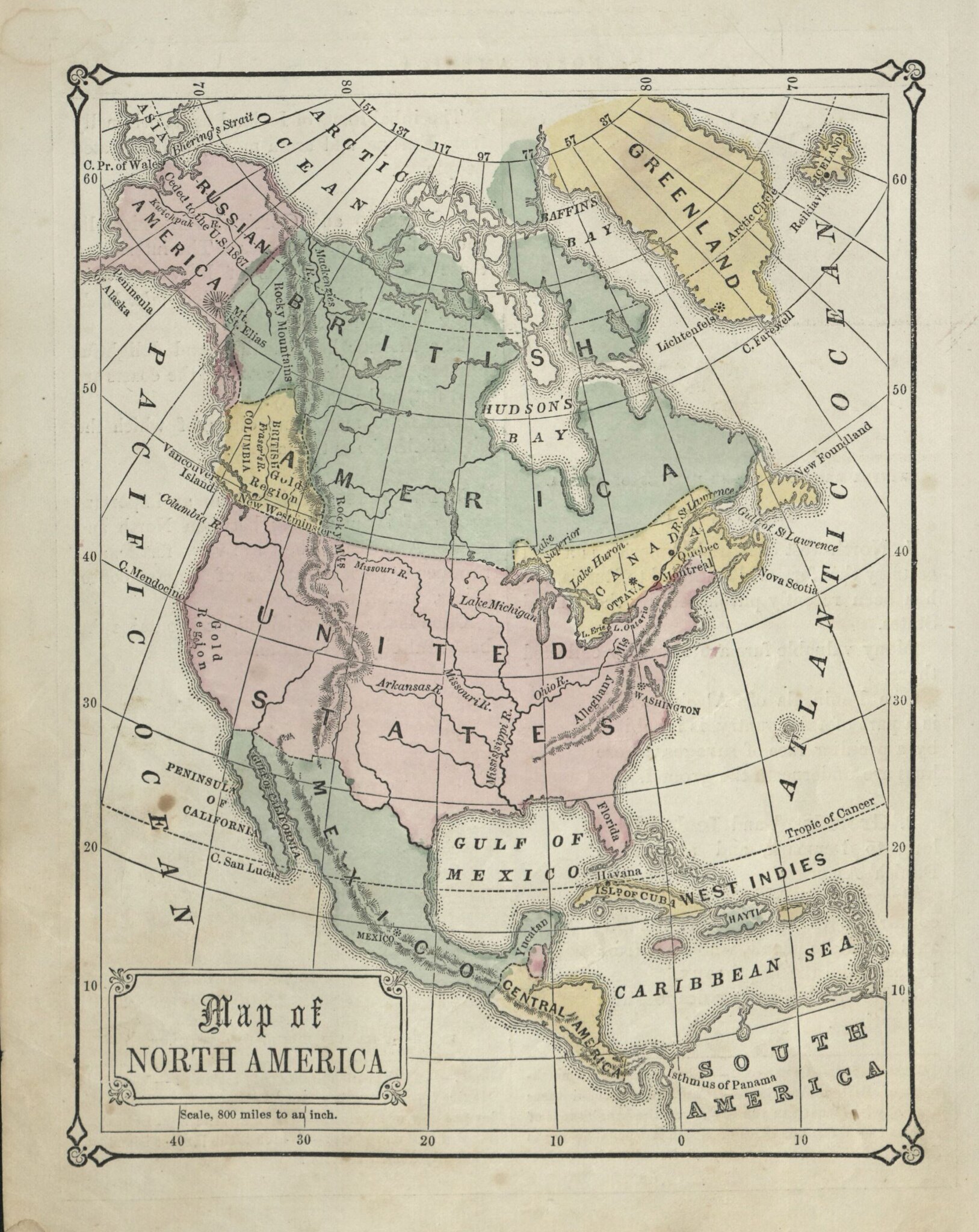

English America

I found this map of North America in a antique store recently, and was going to post it simply because it looked nice and because it refers to Canada as "English America," which seems remarkably apt. Soon after, though, I found another map in a US geography textbook [below left] showing an even more detailed division between Canada and British America. At which point I went back and checked a map we posted several months ago in which much of Canada appears as "New Britain." To figure out what was going on I asked fellow SOAS alum, citizen of the world and lifelong Canadian Laura Clinton. She provided the following guest post, which represents our blog's first serious foray into Canadian history. Ottomanists, meanwhile, are invited to comment on why Turkish so regularly seems to prefer England/English over Britain/British.

"At first glance, a map depicting “British America” might seem confusing. One’s immediate reaction might be to write-off this cartographic anomaly with the easy explanation that everything that lies east of the Pacific and west of the Atlantic is somehow classified as America in some capacity, whether it be North, Central, South, or even United States of.

"While this general assessment is true, it doesn’t explain the difference between British America, and what looks like a hilariously diminutive Miniature Canada featuring the fledgling cities of Ottawa, Montreal and Quebec City in the same map. The crux of the real explanation is that, much like our southern neighbour[sic], modern-day Canada is a construct of several struggling and fragmented settler colonies unified over several wars and protracted negotiations which existed in various incarnations of statehood before resulting in the hockey-and-poutine-lovin’ country that we know and fear today.

"As every good Canadian citizen who didn’t fall asleep in Grade 7 History class knows, Canada was originally settled in the late 15th century by European fur traders looking for beaver pelts to make fancy hats from, and subsequently carved up into rudimentary colonies. The British claimed Newfoundland and modern-day Ontario, and the French settled the creatively-titled New France (now known as Quebec and the Maritime provinces). All the boring bits ranging from the Hudson’s Bay basin through to the west coast were amalgamated as a separate colony called Rupert’s Land. The colony was nominally owned by the Hudson’s Bay Company (which made its fortune in the fur trade), and named after the obviously narcissistic first Governor of the company, Prince Rupert of the Rhine. For the benefit the non-North American readers, the Hudson’s Bay Company was a government-like semiautonomous corporation-state, much like the British East India Company.

"New France was eventually ceded to Britain in all its stinky cheese and maple syrup glory soon after the conclusion of the French and Indian War (otherwise known as the North American extension of the Seven Years War), more commonly referred to as the Anglo-French Rivalry in Canada because we don’t like words that make us feel funny inside. Notably, an undeniable consequence of the Anglo-French Rivalry was the depletion of British resources which aided succession efforts during the American Revolutionary War (so you’re welcome ‘Murica!). In 1791, the colonies were united in two separate provinces: Upper Canada (English) and Lower Canada (French) roughly based on their geographic position along the basin of the St Lawrence River. The provinces were subsequently merged into the Province of Canada following the Act of Union in 1841, which is what is illustrated in this map above, as are the separate colonies of British America (in this instance, Rupert’s Land) and British Columbia. This brief period came to an end after the signing of the British North American (BNA) Act in 1867, an occasion widely regarded as the founding of modern Canada as we know it today, which re-fragmented the Province of Canada into its pre-1841 states, namely: Lower Canada (renamed Quebec), Upper Canada (renamed Ontario), New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. Subsequently, the British American colony of Rupert’s Land was annexed to Canada as the North West Territories in 1869, and the west coast colony of British Columbia joined the Canadian confederation in 1871.

*No beavers where harmed in the making of this blog post, but sadly not in the founding of Canada."

"At first glance, a map depicting “British America” might seem confusing. One’s immediate reaction might be to write-off this cartographic anomaly with the easy explanation that everything that lies east of the Pacific and west of the Atlantic is somehow classified as America in some capacity, whether it be North, Central, South, or even United States of.

"While this general assessment is true, it doesn’t explain the difference between British America, and what looks like a hilariously diminutive Miniature Canada featuring the fledgling cities of Ottawa, Montreal and Quebec City in the same map. The crux of the real explanation is that, much like our southern neighbour[sic], modern-day Canada is a construct of several struggling and fragmented settler colonies unified over several wars and protracted negotiations which existed in various incarnations of statehood before resulting in the hockey-and-poutine-lovin’ country that we know and fear today.

"As every good Canadian citizen who didn’t fall asleep in Grade 7 History class knows, Canada was originally settled in the late 15th century by European fur traders looking for beaver pelts to make fancy hats from, and subsequently carved up into rudimentary colonies. The British claimed Newfoundland and modern-day Ontario, and the French settled the creatively-titled New France (now known as Quebec and the Maritime provinces). All the boring bits ranging from the Hudson’s Bay basin through to the west coast were amalgamated as a separate colony called Rupert’s Land. The colony was nominally owned by the Hudson’s Bay Company (which made its fortune in the fur trade), and named after the obviously narcissistic first Governor of the company, Prince Rupert of the Rhine. For the benefit the non-North American readers, the Hudson’s Bay Company was a government-like semiautonomous corporation-state, much like the British East India Company.

"New France was eventually ceded to Britain in all its stinky cheese and maple syrup glory soon after the conclusion of the French and Indian War (otherwise known as the North American extension of the Seven Years War), more commonly referred to as the Anglo-French Rivalry in Canada because we don’t like words that make us feel funny inside. Notably, an undeniable consequence of the Anglo-French Rivalry was the depletion of British resources which aided succession efforts during the American Revolutionary War (so you’re welcome ‘Murica!). In 1791, the colonies were united in two separate provinces: Upper Canada (English) and Lower Canada (French) roughly based on their geographic position along the basin of the St Lawrence River. The provinces were subsequently merged into the Province of Canada following the Act of Union in 1841, which is what is illustrated in this map above, as are the separate colonies of British America (in this instance, Rupert’s Land) and British Columbia. This brief period came to an end after the signing of the British North American (BNA) Act in 1867, an occasion widely regarded as the founding of modern Canada as we know it today, which re-fragmented the Province of Canada into its pre-1841 states, namely: Lower Canada (renamed Quebec), Upper Canada (renamed Ontario), New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. Subsequently, the British American colony of Rupert’s Land was annexed to Canada as the North West Territories in 1869, and the west coast colony of British Columbia joined the Canadian confederation in 1871.

*No beavers where harmed in the making of this blog post, but sadly not in the founding of Canada."

↧

↧

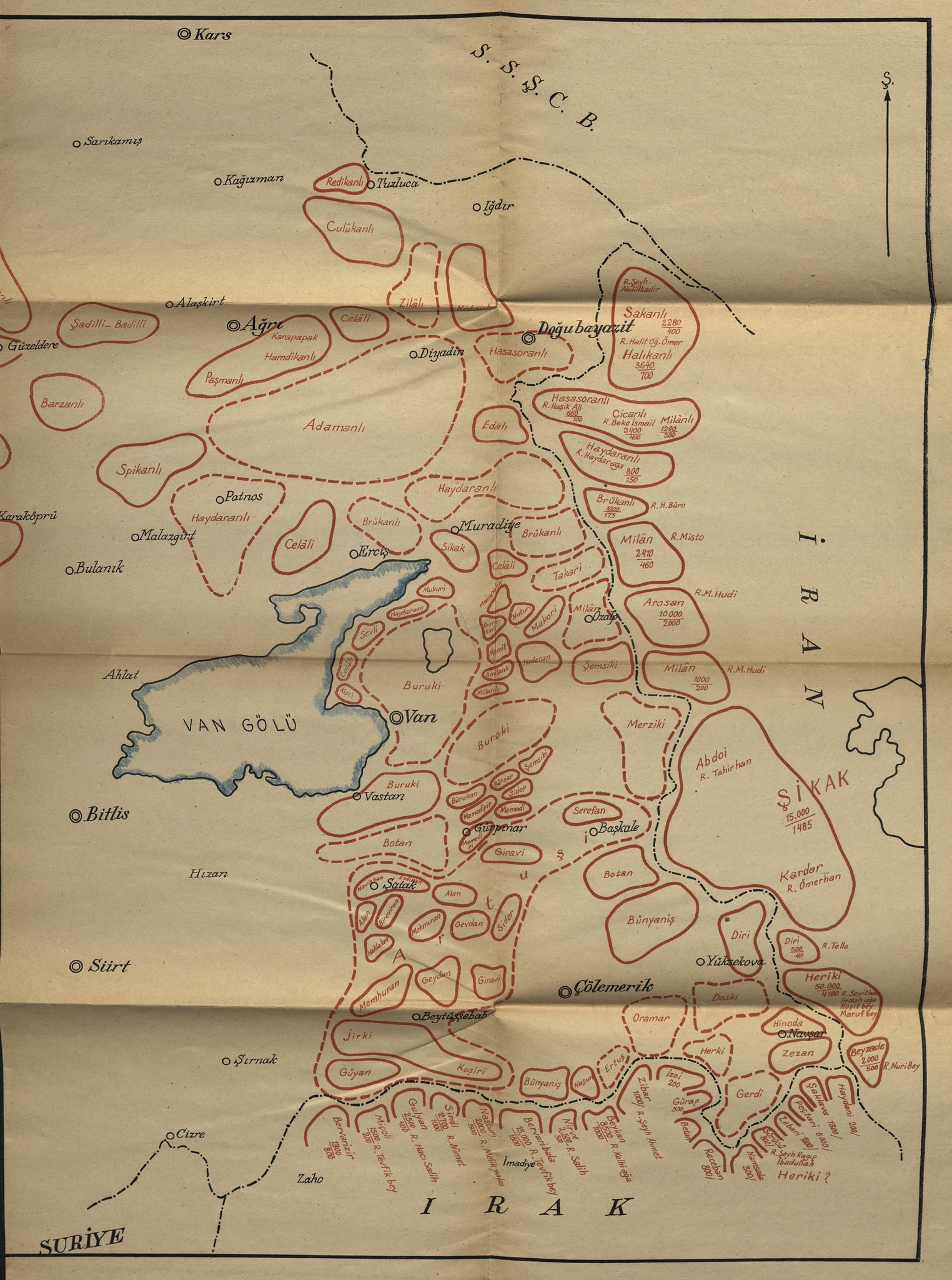

Rebellious Tribes of Eastern Anatolia

(See a full-size version of this map can be found here, along with the map's western half, showing Dersim, here. Another map in the book's appendix shows the various rebellions featured in the text.)

Today's map today comes from a book entitled "Doğu bölgesindeki geçmiş isyanlar ve alınan dersler" or "Rebellions that have taken place in the Eastern region and their lessons," published in 1946 by the Turkish General Staff. The legend explains that tribes marked in dotted red lines are "those who have been involved in rebellions up until the present" while tribes in solid red are "those not involved in rebellions up until the present." Phrased like this, of course, it's hard to avoid the implication that for the other still docile tribes it could just be a matter of time. Indeed, one of the more interesting points that comes out of Reşat Kasaba's Moveable Empire is that the Ottoman state's efforts to break the power of Eastern Anatolian tribes were hobbled by a fundamental contradiction: in fighting rebellious tribes the state relied on the support of loyal tribes, which where thereby strengthened through their alliance with the state and the removal of their tribal rivals. In this context it is interesting to read in Ümit Üngör's Making of Modern Turkey that while the Republican government certainly relied on tribal allies in fighting rebellions in the 20s and 30s, it also distinguished itself from the Ottoman state in its willingness to deport members of even loyal tribes from Eastern Anatolia.

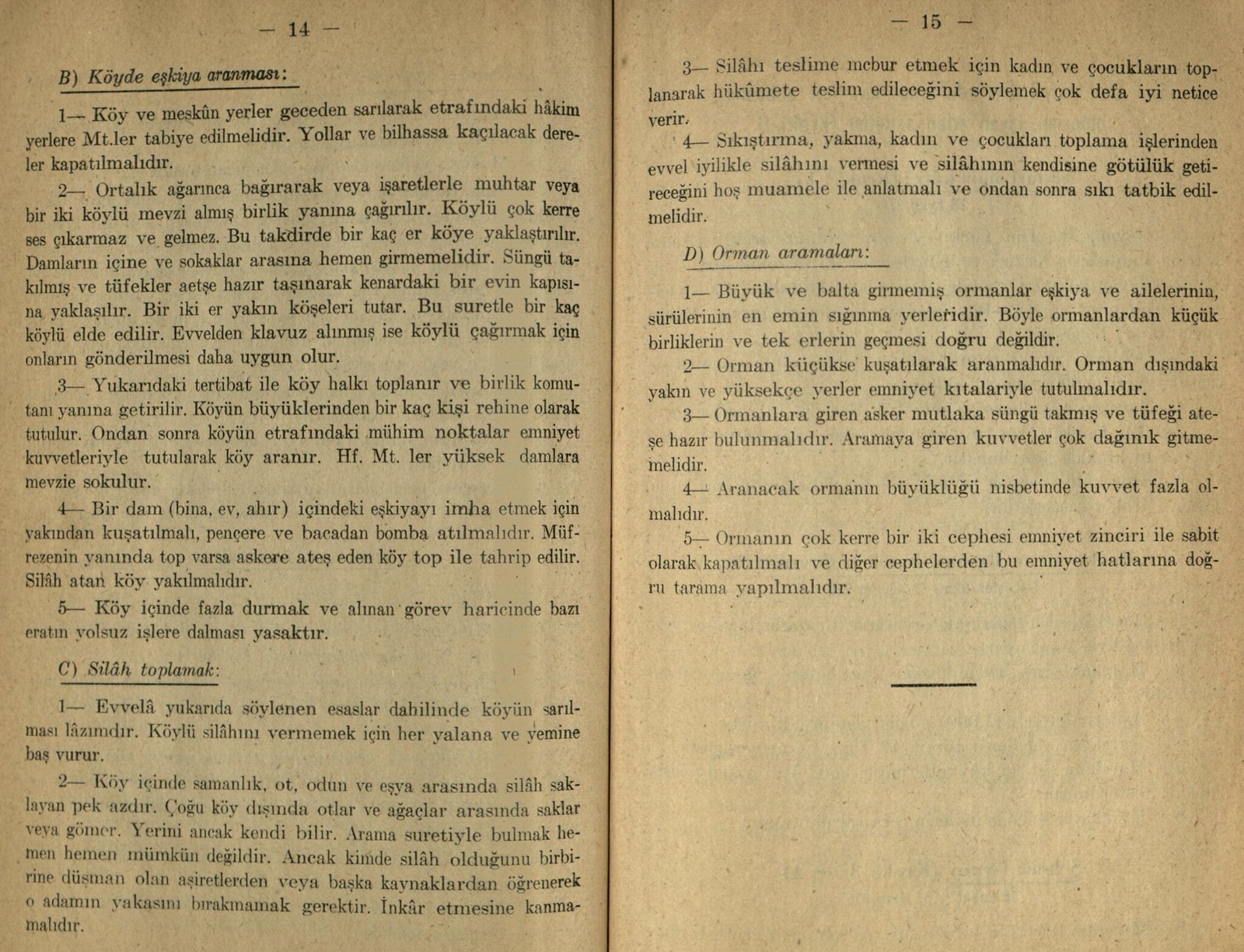

"Doğu bölgesindeki geçmiş isyanlar ve alınan dersler" itself is largely devoted to straightforward military advice for fighting a guerrilla war, covering such topics as scouting, defensive measures in bad terrain and avoiding ambushes. The conclusion also features a brief summary of the major rebellions the Turkish Army faced, almost all of which are attributed to British intrigue. Perhaps most striking today is the section below, concerning treatment of local villages. Today there are still many scholars doing important work in publicizing the brutality of the Turkish state during the one-party era, yet at the same time there are others for whom it seems casual and often insufficiently contextualized attacks on Kemalist authoritarianism have become an end in themselves. In this context I would only say that I highlight the passage below not to suggest that the Turkish military was doing anything that any other army facing an insurgency in the 20th century didn't, but rather because the manual's remarkable candor should help force us to confront the kind of systematic violence that far too many people continue to suffer in civil wars around the world. A translation of the text appears below.

B) Searching for bandits in a village

1. The village and inhabited areas should be surrounded at night and mechanized guns should be placed around it in commanding locations. Roads and especially stream beds through which escapes could occur must be closed.

2. As dawn breaks the muhtar [village headman] or one or two villagers should be called to the unit’s position by means of shouting or signals. Generally villagers remain silent and do not come. In this case a few soldiers should be sent toward the village. They should not immediately enter the structures or between the streets. With bayonets mounted and guns ready to fire they approach the door of an outer house. One or two soldiers cover the corners. In this manner a few villagers are obtained. If a guide has earlier been obtained, sending him to obtain villagers is more suitable.

3. In the aforementioned manner the village’s population is gathered and brought to the unit’s commander. A few from among the village notables are taken as hostages. After that the village is searched while the important positions around the village are covered by a security force. Light mechanized guns are positioned on high roofs.

4. To destroy bandits located indoors (buildings, houses, stables) these structures should be approached and bombs should be thrown in the windows or down the chimneys. If the detachment has artillery, villages firing on soldiers should be destroyed with the artillery. Villages opening fire should be burned.

5. It is forbidden for soldiers to remain unnecessarily within the village for anything other than what is ordered and to engage in corrupt business.

C) Gathering weapons

1. It is necessary to surround the village according to the principles stated above. Villagers resort to every lie and promise to avoid giving up their guns.

2. Those hiding their guns in hay, feed, wood or belongings within the village are few. Most hide and bury their guns in fields and forests outside the village. They are almost impossible to find through searching. Rather those who have weapons must be identified from rival tribes or other sources and then pressured. Their denials must not be believed.

3. Often gathering their wives and children and saying they will be handed over to the government is effective in forcing them to surrender their guns.

4. Before pressuring, burning or gathering women and children, positive means should be used to secure weapons. It should be explained in a friendly manner that guns will bring their owners trouble and this should then be made certain.

Nick Danforth, Georgetown University

Today's map today comes from a book entitled "Doğu bölgesindeki geçmiş isyanlar ve alınan dersler" or "Rebellions that have taken place in the Eastern region and their lessons," published in 1946 by the Turkish General Staff. The legend explains that tribes marked in dotted red lines are "those who have been involved in rebellions up until the present" while tribes in solid red are "those not involved in rebellions up until the present." Phrased like this, of course, it's hard to avoid the implication that for the other still docile tribes it could just be a matter of time. Indeed, one of the more interesting points that comes out of Reşat Kasaba's Moveable Empire is that the Ottoman state's efforts to break the power of Eastern Anatolian tribes were hobbled by a fundamental contradiction: in fighting rebellious tribes the state relied on the support of loyal tribes, which where thereby strengthened through their alliance with the state and the removal of their tribal rivals. In this context it is interesting to read in Ümit Üngör's Making of Modern Turkey that while the Republican government certainly relied on tribal allies in fighting rebellions in the 20s and 30s, it also distinguished itself from the Ottoman state in its willingness to deport members of even loyal tribes from Eastern Anatolia.

"Doğu bölgesindeki geçmiş isyanlar ve alınan dersler" itself is largely devoted to straightforward military advice for fighting a guerrilla war, covering such topics as scouting, defensive measures in bad terrain and avoiding ambushes. The conclusion also features a brief summary of the major rebellions the Turkish Army faced, almost all of which are attributed to British intrigue. Perhaps most striking today is the section below, concerning treatment of local villages. Today there are still many scholars doing important work in publicizing the brutality of the Turkish state during the one-party era, yet at the same time there are others for whom it seems casual and often insufficiently contextualized attacks on Kemalist authoritarianism have become an end in themselves. In this context I would only say that I highlight the passage below not to suggest that the Turkish military was doing anything that any other army facing an insurgency in the 20th century didn't, but rather because the manual's remarkable candor should help force us to confront the kind of systematic violence that far too many people continue to suffer in civil wars around the world. A translation of the text appears below.

B) Searching for bandits in a village

1. The village and inhabited areas should be surrounded at night and mechanized guns should be placed around it in commanding locations. Roads and especially stream beds through which escapes could occur must be closed.

2. As dawn breaks the muhtar [village headman] or one or two villagers should be called to the unit’s position by means of shouting or signals. Generally villagers remain silent and do not come. In this case a few soldiers should be sent toward the village. They should not immediately enter the structures or between the streets. With bayonets mounted and guns ready to fire they approach the door of an outer house. One or two soldiers cover the corners. In this manner a few villagers are obtained. If a guide has earlier been obtained, sending him to obtain villagers is more suitable.

3. In the aforementioned manner the village’s population is gathered and brought to the unit’s commander. A few from among the village notables are taken as hostages. After that the village is searched while the important positions around the village are covered by a security force. Light mechanized guns are positioned on high roofs.

4. To destroy bandits located indoors (buildings, houses, stables) these structures should be approached and bombs should be thrown in the windows or down the chimneys. If the detachment has artillery, villages firing on soldiers should be destroyed with the artillery. Villages opening fire should be burned.

5. It is forbidden for soldiers to remain unnecessarily within the village for anything other than what is ordered and to engage in corrupt business.

C) Gathering weapons

1. It is necessary to surround the village according to the principles stated above. Villagers resort to every lie and promise to avoid giving up their guns.

2. Those hiding their guns in hay, feed, wood or belongings within the village are few. Most hide and bury their guns in fields and forests outside the village. They are almost impossible to find through searching. Rather those who have weapons must be identified from rival tribes or other sources and then pressured. Their denials must not be believed.

3. Often gathering their wives and children and saying they will be handed over to the government is effective in forcing them to surrender their guns.

4. Before pressuring, burning or gathering women and children, positive means should be used to secure weapons. It should be explained in a friendly manner that guns will bring their owners trouble and this should then be made certain.

Nick Danforth, Georgetown University

↧

The Soviet National Delimitation in Central Asia

"All to the elections!" declares this Soviet propaganda poster from 1957. A couple reads a newspaper called "Soviet Tajikistan" while a banner over what is presumably the polling place reads "Welcome" (Thanks to Masha Kirasirova for the translation). Soviet policy in Central Asia sought to create states that were "national in form, Soviet in content." In the eyes of critics, this meant getting to wear your Tajik cap while reading a Soviet newspaper or use traditional Tajik instruments to celebrate a rigged election.

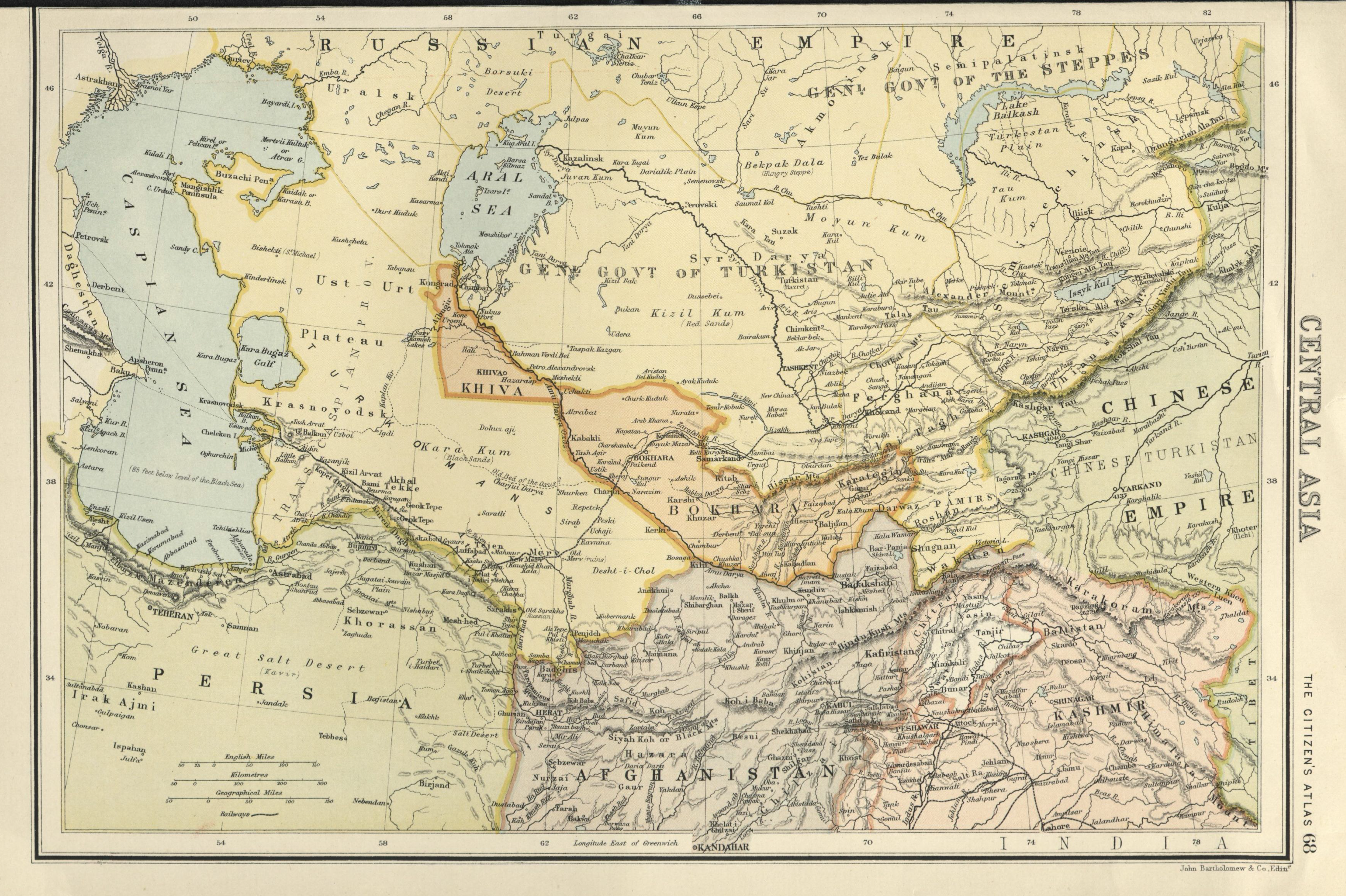

Today we are publishing the first in a new series of short articles designed to highlight work that because of its focus, style or reliance on visual sources are unsuitable for standard academic journals. We welcome contributions, map related or otherwise, and hope that we can serve as an outlet for exciting compelling work that wouldn't get seen otherwise. The first of these papers offers a brief look at how the Soviet Union went about creating the states that constitute Central Asia today. It's a subject of both controversy and confusion, as well as a source of curiosity for anyone who has ever looked at a map of the region (left). I hope this paper can offer the clearest possible overview of the complicated transformations that occurred in the region between Czarist conquest in the 19th century and the official political reorganization that occurred under Stalin's direction in the 1920s. You can download the essay as a PDF or view it after the break. But first, in addition to the remarkable propaganda poster above, the second of our two maps, showing Central Asia before the Soviet national delimitation.

Today we are publishing the first in a new series of short articles designed to highlight work that because of its focus, style or reliance on visual sources are unsuitable for standard academic journals. We welcome contributions, map related or otherwise, and hope that we can serve as an outlet for exciting compelling work that wouldn't get seen otherwise. The first of these papers offers a brief look at how the Soviet Union went about creating the states that constitute Central Asia today. It's a subject of both controversy and confusion, as well as a source of curiosity for anyone who has ever looked at a map of the region (left). I hope this paper can offer the clearest possible overview of the complicated transformations that occurred in the region between Czarist conquest in the 19th century and the official political reorganization that occurred under Stalin's direction in the 1920s. You can download the essay as a PDF or view it after the break. But first, in addition to the remarkable propaganda poster above, the second of our two maps, showing Central Asia before the Soviet national delimitation.

An Overview of Soviet Nationality Policy in Central Asia:

the transformation and suppression of identities in advance of delimitation.

“The [Pan-Islamists] want to create one Muslim millat by joining together the [various] Muslim millats…. Generally, is it possible to unite the millats? No!... To create a millat in an artificial form is impossible.” -- Alash Orda leader Jihanshah Dosmaghembet-uli, 1917 (1)

“The Turkish tribes of Turkestan who aspire to unite have been split up into separate “nations” and in place of national self determination there took place inter-tribal demarcation within one nationality.” -- Former President of the Khokand Autonomy Mustafa Chokayev, 1931 (2)

There are two principle views of the Soviet national delimitation process in Central Asia. The first holds that the Soviets suppressed the Central Asians’ true national identity by dividing them into invented “nations,” as part of cynical plan to divide and conquer. The second holds that the Soviets made an earnest effort to build new nations where none had existed, and acted in accordance both with their own scientific logic and, to a lesser extent, the wishes of indigenous elites. (3)

An examination of the events leading up to the delimitation shows that there is truth to both claims. As the above quotes demonstrate, the Central Asians themselves were divided on how to incorporate their diverse pre-modern identities into a world where nation-states had a growing monopoly on international legitimacy. There is no way to know how they would have resolved the issue if left to their own devices. Given the Soviets’ desire to control Central Asia, and given the way they applied their nationality policy to the rest of the former Czarist Empire, it is inevitable that the they would have intervened decisively in this debate to create nation-states where none had existed before. In trying to understand why the Soviets intervened in the way that they did, it is important to look not at the delimitation itself but at the events leading up to it. By 1920, the decision to suppress Pan-Turkic identity – the defining aspect of the delimitation for its critics – had already been made and the broad features of the delimitation already rendered inevitable.

Before the arrival of the Russians in Central Asia, political power was generally exercised by the leaders of clans or tribes whose membership was determined by real or imagined genealogies. In the south, the Khanates of Khiva, Bukhara, Kokhand and Mir were organized along dynastic lines and ruled Emirs who pledged to uphold Islamic values and exercised power over whoever’s obedience he could compel.

Within this broad political structure, a wide range of personal identities existed. First and foremost among these was the religious one. With the exception of a small number of Jews, Nestorians and Manicheans, almost all the native inhabitants were at least nominally Muslims. Because Islamic identity was so widespread, it had little use as a basis for political organization before the arrival of Russian soldiers and settlers during the 19th century. For many Muslim Central Asians, Russian colonial expansion in the 19th century was seen in religious terms, with the outsiders being thought of interchangeably as Russians, Christians and non-Muslims. Nonetheless, there is little evidence of religious rhetoric in any of the major anti-imperial movements that occurred before the First World War.

Another important form of pre-national identity was rooted in the split between sedentary and nomadic societies. Amongst nomads, the term sart was used to refer settled populations, whatever their tribal or ethnic origins. In this way, if a Turkmen or Kyrgyz tribe took up agriculture, its members would also become sarts. The tribal and clan-based political units into which much of Central Asia’s population was divided seldom transcended this split, though the city-based Khanates occasionally extended a limited degree of control over nomadic groups living on the fringes of their domains.

For many Russian and European observers, though, the most interesting and important forms of identity were the supposed racial or ethnic categories that were later transformed into Soviet nationalities. (4) 19th century travellers and ethnographers each divided Central Asia’s population in a slightly different way, but their classifications were almost always drawn from the following list of terms: Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Turkmen, Tajik, Uzbek, Sart, Turk, as well as smaller groups like the Kara-Kalpaks and the Kurama. Given their unique history and the importance they would take on, each term requires an explanation of its own. The Kazakhs (who he Russians originally called Kyrgyz, or sometimes Kazakh-Kyrgyz to avoid confusion with the Cossacks, but who later became simply Kazakhs), the Kyrgyz (originally the Kara-Kyrgyz, later simply the Kyrgyz after the Kazakh-Kyrgyz became Kazakhs) and the Turkmen were all tribal confederations that defined themselves according to myths of common ancestry. (5) Though the Turkmen, for example, all claimed descent from a common ancestor, Oghuz, they were divided into a number of tribes such as the Tekes, Salirs and Yomuts. These tribes, though subdivided into smaller family units, served as the primary units of political organization and often fought against one another. (6) Similarly, the Kazakhs were divided into the Great, Small and Middle hordes, with these hordes in turn made up of smaller tribal groups. (7)

Among the settled population principally located between the Amu and Syr Darya, the situation was even more complex. Some ethnographers assumed that sart was an ethnic/racial category and tried to identify their defining linguistic and physical features. More frequently, however, the population was broken down between Tajik and Uzbek or alternatively Tajik and Turk. This classification could be based on either linguistic or racial features, with the Tajiks being either Persian speakers or those of Persian descent, and the Uzbeks/Turks being Turkic speakers or those of Turkic descent. Either definition caused considerable confusion, as not only had Turkic and Persian tongues considerably influenced one another, but many individuals were themselves bilingual, with Persian being more prevalent among the urban and educated. In rural areas, where tribes often carried fixed ethnic identities, it was possible to find Persian-speaking Uzbeks, while city dwellers without tribal identities often became Tajiks by default. (8) The term Uzbek could be used interchangeably with “Turk” to designate all those who spoke a Turkic language and were not marked as being a member of one of the tribal confederations discussed above. Conversely, the terms could also be used separately, with the term Uzbek referring to self-proclaimed descendants of the Uzbek tribe which had conquered the region in the 15th century, and “Turk” referring to those already living in the area at the time. In this sense, the Emirs of the southern Khanates, and even occasionally the leaders of Turkmen tribes, referred to themselves as Uzbeks, since it implied descent an earlier ruling elite.

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, these pre-modern identities were transformed and reconfigured. Some indigenous leaders began to think of their ethnic identities in nationalist terms while others developed a new Pan-Turkic national identity that often merged with the increasingly politicized Islamic identity that had emerged. Many of these new forms of identity became the basis of short-lasting political entities during the turbulent years of the Russian Revolution.

Pan-Turkism and Pan-Islamism developed together as part of the Jadid movement, a religious-political reform effort spearheaded first by Tatar intellectuals and later embraced Central Asians as well. Jadidism, to the extent that it had a coherent doctrine, encouraged educational reform and Islamic piety with the aim of creating a new form of Western-oriented Islam that would help liberate Central Asians from the subordinate status they suffered under Russian colonialism. In the early years of the 20th century, Jadidism became increasingly anti-colonial, demanding greater autonomy for the people of Central Asia and an end to the oppressive land appropriations that had brought hardship to many Kazakhs.

By the end of the 19th century, the Jadidis became increasingly aware of a number of trends taking place in the world around them, including the rise of nationalist ideologies in Europe and the spreading colonization of Muslim lands. This led to the revival of the traditional concept of the Muslim Umma as a political unit whose shared needs could be achieved through united action. Simultaneously, the growth of European Turcology and the rise of Turkish nationalism in the Ottoman Empire made it possible to imagine a new shared identity for all those with a common Turkic language and culture. Given the considerable overlap between Turkic culture and Islamic faith in the Russian Empire, these two identities were by no means exclusive when use, as they generally were, within a limited geographic context. To facilitate education, communication and unity among the people of Central Asia, the Jadidis set out to create a common standard Turkic language. In the 1880s, the Crimean Jadidi Ismail Gaspirali promoted a simplified form of Turkish called the “unified” [tawdid] or “common” [umumi] language. (9)

Many Central Asian Jadidis embraced this “middle dialect,” [orta shiwa] but for others it became a source of resentment. In the Kazakh steppe, where Tatar intellectuals had been active for most of the century, resentment had gradually developed against the perceived condescension with which the Tatars viewed the local Kazakhs. Leaders like Akmet Baytursin-uli argued for a more local form of nationalism in which the Kazakh nation would develop its own language, based on the dialect spoken amongst people on the steppe, not people in Crimea or Anatolia.

Until the First World War, the impact of Pan-Turkist and Pan-Islamist thought was frequently confined to the pages of a number of sporadically published journals that struggled to overcome the dual threats of Czarist censorship and insolvency. Kazakh nationalists made similar efforts, publishing a string of journals and gazettes with such earnestly nationalistic titles as Kazakh Gaziti, Kazakhstan, and Kazakh. (10) Between 1905 and 1906 the Jadidis took more concrete political action, convening three All-Russian Muslim congresses in order to protect the “religious and cultural” rights of Muslims through the “quasi-constitutional means allowed by the October Manifesto.” (11) After a period of repression, a Fourth Muslim Conference was convened in 1914, but very few Central Asians attended.

The situation changed dramatically with the power vacuum that followed the February Revolution in 1917. The revolutionary groups that seized power in Tashkent and Orenburg (capitals of the Czarist administrative territories covering Turkestan and the Kazakh Steppe respectively) were largely composed of Russian soldiers and workers. At a time of devastating famine, these new governments were chiefly concerned with feeding the Russian settlers and were quick to requisition food from the natives whenever necessary. In response to these conditions, a group of Jadidis convened the Fourth Extraordinary Regional Muslim Congress in Khokand, where, on November 17th, they proclaimed an autonomous government of Turkestan (the Khokand Autonomy) “in union with the Federal Democratic Russian Republic.” (12) Its hurried efforts to procure arms, funds and soldiers, as well as its appeal for support from the Soviet government in St. Petersburg, came to naught when forces from the Tashkent government took Khokand in February of the next year. A similar fate awaited the Turcoman National Committee, organized by nationalist intellectuals and military leaders in Transcaspia under the guise of providing aid to native famine victims. When the Committee set out to create a Turcoman National Army in February 1918, it too was crushed by a military detachment from Tashkent. Kazakh nationalists fared only slightly better. In 1917, the Alash Orda, a political party founded by Kazakh Jadidis in 1905, established a native government and joined the Whites in fighting against Bolshevik authority in the Kazakh step. (13) In late 1919, when their military position became precarious, the Alash Orda accepted a reconciliatory offer from the Bolsheviks and soon allowed their territory to be incorporated into the Moscow government as an autonomous region.

Though the actions of the revolutionary governments that took power in Turkestan and the Steppe provoked native resistance, many of the Jadidis were sympathetic to Bolshevism on an ideological level. Many also felt that autonomy under Russia control would be preferable to independent states under the control of the conservative clergy, who had themselves become increasingly active in regional politics. Pursing the same tactic it would use with the Alash Orda, the Moscow government sought to play to these sympathies and increase its control over Turkestan by incorporating educated natives who may have at first opposed the Bolsheviks into the Russian Communist Party. The Jadidis responded enthusiastically, though not always in the way the Moscow government had hoped. In May of 1919, the first conference of Muslim Communists of Central Asia, convened under the leadership of Turar Ryskulov and Tursun Khojaev, spoke out against the Bolshevik’s attitude toward the indigenous people, saying they were treated as “subjects.” (14) Over the next year, the party’s ranks swelled with Muslim members. In January of 1920, at the Fifth Regional Congress of the Communist Party of Turkestan, these Muslim communists passed a resolution renaming the Turkestan Autonomous Republic the Autonomous Turkic Republic, with Ryskulov explicitly comparing the autonomy he was demanding to that previously sought by the Khokand Autonomy. (15)

The Soviets responded vigorously. The Moscow government, having already received a telegram from their emissary Mikhail Frunze warning that “concessions made to the Muslims would encourage the anti-Soviet Basmachi movement,” (16) decided in June of 1919 to purge Ryskulov and his followers from the party, accusing them of nationalist deviations and supporting the Basmachis. The regional Muslim Bureau, which had come under the control the Muslim Communists, was dissolved. In 1921, the Tenth Party Congress denounced Pan-Turkist thought as a deviation, and in 1923, Stalin launched an “all –out campaign against Turkic nationalism,” in which Sultan Galiev, then the leading Muslim National Communist, was arrested.(17) Despite the Muslim National Communists protestations of loyalty, the Moscow leadership had decided that their commitment to Islam and nationalism was more sincere than their commitment to communism. (18) The historic continuum between Jadisism, Pan-Islamism, Pan-Turkism and anti-imperialism, coupled with the ongoing calls for Pan-Turkic autonomy, was threat that the Bolsheviks would not accept. (19)

After the decision to suppress Pan-Turkism had been reached, it was hardly surprising that the sub-Turkic ethnic identities that had been identified before the revolution became the basis of the post-delimitation Soviet republics. In the case of the Kazakhs, the transformation from ethnic to national identity had already occurred indigenously, as it had to a lesser extent amongst the Turkmen elite. After trying to unite Turkestan’s sedentary population within the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic, (which was dominated by Young Bokharan Jadidis, whose sense of national identity had already begun to cohere within Emirate of Bokhara and the Bokharan People’s Soviet Republic (20)) the Soviets then took the alternative approach in 1929 of creating an independent Tajik SSR based on the same ambiguous ethnic and linguistic criteria that had been used to distinguish the Tajiks as a race in the 19th century. Some decisions, for example creating a full republic for the Kyrgyz but not the Kara-Kalpacks, could have been made differently, but the overall impact would have been similar. (21) There was, in short, nothing particularly Machiavellian in the way the Soviets divided Turkestan, only in the fact they divided it at all.

Footnotes

1 Quoted by Edward Allworth, “The ‘Nationality’ Idea in Czarist Central Asia,” 247. From Butun rosiya mulumanlarining 1917inchi yilda 1-11 mayda maskawdaumumi isyezdining protaqollari (Pterograd: “amanet” Shirkati Matbu’asi, 1917)197.

2 Mustapha Chokaiev, “Turkestan and the Soviet Regime,” in the Journal of the Royal Central Asian Society, 18 (1931), 414.

3 In the article cited above, Mustapha Cokaiev presents this view based on his first hand experience of the events in question. More recently, Oliveir Roy gives a post-Soviet variant of the argument in The New Central Asia: The Creation of Nations. Baymirza Hayit’s Some Problems of Modern Turkestan History, discusses the Soviet-era historiographical debate over this and related issues with some passion. For the other side of the argument, Adrienne Edgar’s The Making of Soviet Turkmenistan gives the best account.

4 See, for example, K. K. Pahlen’s Mission to Turkestan, or Annette Meakin’s In Russian Turkestan.

5 Adeeb Khalid, The Politics of Muslim Cultural Reform, 188.

6 In The Making of Soviet Turkmenistan, Adrienne Lynn Edgar calls them “primary sources of solidarity and mutual assistance.” Edgar, 21.

7 Martha Brill Olcott, The Kazakhs 9-16.

8 Khalid gives the most concise explanation of this, though Guissou Jahangiri’s article on “The Premise for the Construction of a Tajik National Identity, 1920-1930” in Djalili, Grare et al.’s Tajikistan: The Tirals of Independence, is perhaps more thorough.

9 Allworth, “The ‘Nationality’ Idea…” 238.

10 Allworth, “The ‘Nationality’ Idea…” 244.

11 Khalid, 231.

12 Khalid 275.

13 Alash was the name of the legendary common ancestor of all three Kazakh hordes. Hence the name “Alash Orda,” (meaning the Horde of Alash) reveals how traditional genealogical ties could be reconfigured into national identities.

14 Helene Carrere d’Encasse, “Civil War and New Governments,” in Allworth’s Central Asia, 233. 15 Khalid, 296.

16 D’Encasse, 234.

17 Symour Becker, “National Consciousness and the Politics of the Bukhara People’s Conciliar Republic,” 165.

18 For more on this point, see Bennigsen and Wimbush, Muslim National Communism in the Soviet Union, particularly chapter 3, or for a contemporary account Joseph Castagne’s Le Turkestan Dupuis la Revolution Russe.

19 This was not a case of divide and rule per se. The idea of a territorially united Turkestan was not seen as inherently problematic, rather it was the historic and political connotations that idea carried among its native advocates.

20 Timur Kocaoglu, “The Existence of a Bukharan Nationality in the Recent Past,” 151 – 157.

21 Roy, for example, cites the complexity – perhaps squigglyness is the better word – of the Central Asian borders as evidence of malign Soviet intentions. In fact, such borders are likely to occur whenever states are created by a central authority trying to divide ethnic groups along “scientific” lines, instead of through warfare, which often dictates more “natural,” defensible boundaries. Edgar, by contrast, makes much of the fact that the borders of the Central Asian republics were drawn with the participation of local leaders, who often fought vigorously on behalf of their newfound nationalities. This was no doubt true, but all it proves is that if the delimitation was part of a policy of divide and conquer, it was effective.

Bibliography

Allworth, Edward (ed.).Central Asia: 120 Years of Russian Rule. Duke University

Press, Durham, 1989.

-- The Modern Uzbeks. Hoover Institution Press, Stanford, 1990.

-- (ed.).The Nationality Question in Soviet Central Asia. Praeger, New York,

1973.

-- “The ‘Nationality’ Idea in Czarist Central Asia” in Goldhagen, Ethnic Minorities in the Soviet Union, 229-250.

Becker, Symour. “National Consciousness and the Politics of the Bukhara People’s

Conciliar Republic,” in Allworth, Edward, The Nationality Question in Soviet

Central Asia. 159 – 167.

Castagne, Joseph. Le Turkestan Depuis La Revolution Russe, Ernest Laroux, Paris,

1922.

Chokaiev, Mustapha. “Turkestan and the Soviet Regime,” in the Journal of the Royal

Central Asian Society, 18 (1931), 414.

Edgar, Adrienne Lynn. The Making of Soviet Turkmenistan. Princeton University

Press, Princeton, 2004.

d’Encasse, Helene Carrere. “Civil War and New Governments,” in Allworth, Edward,

Central Asia: 120 Years of Russian Rule, 224 -253.

Goldhagen, Erich (ed.). Ethnic Minorities in the Soviet Union. Praeger, New York,

1968.

Hayit, Baymirza. Some Problems of Modern Turkestan History.

Khalid, Adeeb. The Poltics of Muslim Cultural Reform: Jadidism in Central Asia.

University of California Press, Berkely, 1998.

Kocaoglu, Timur. “The Existence of a Bukharan Nationality in the Recent Past,” in Allworth, Edward, The Nationality Question in Soviet Central Asia. 151 – 167.

Manz, Beatrice. Central Asia in Historical Perspective. Westview Press, San

Francisco, 1994.

Meakin, Annette. In Russian Turkestan: A Garden of Asia and Its People. George

Allen, London, 1903.

Mohammad-Reza Djalili, Frederic Grare et al. (ed.). Tajikistan: The Trials of

Independence. Curzon, Surrey, 1998.

Olcott, Martha Brill. The Kazakhs. Hoover Institution Press, Stanford, 1987.

Pahlen, K. K.. Mission to Turkestan, Oxford University Press, London, 1964.

Park, Alexander. Bolshevism in Turkestan: 1917 – 1927. Columbia University Press, New York, 1957.

↧

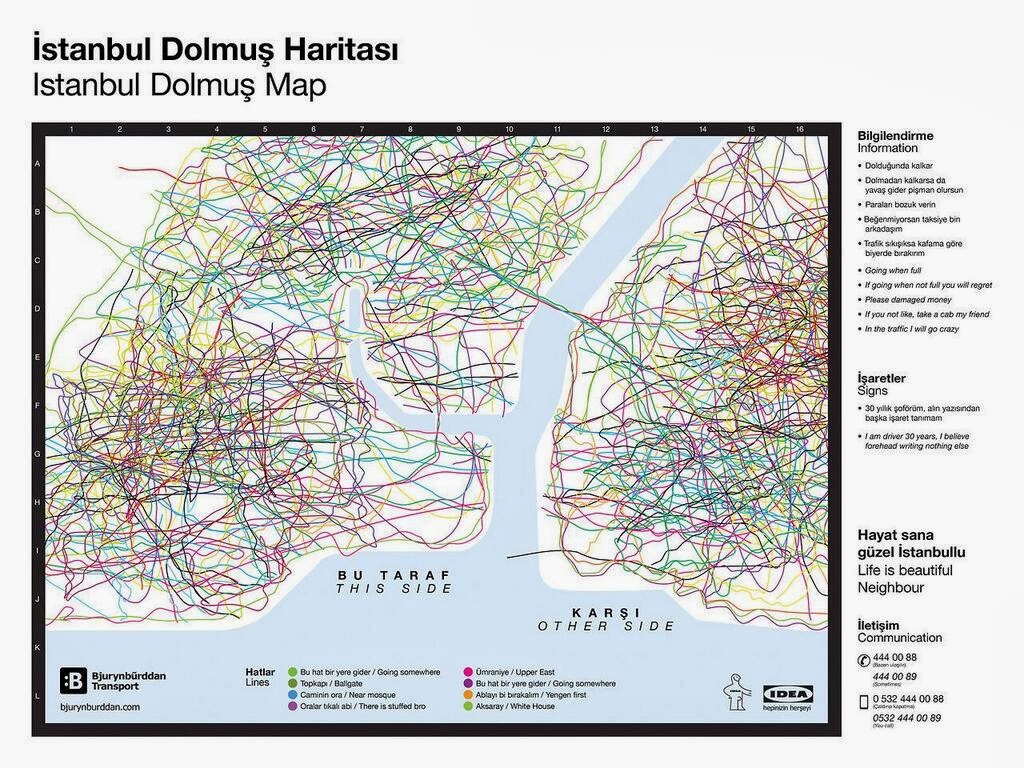

Dolmuş Haritası

A fantastic map that we felt obligated to post, originally made by the folks at Bjurynburddan and pointed out to us by Elizabeth Angell. Far more exciting, in any case, than the one below, which might actually be accurate, but costs 10 lira.

↧

Molla Nasreddin Satire Map

This map is from the magazine Molla Nasreddin, an early 20th century satirical magazine from Baku that's gotten a some attention recently. The caption reads "The States of the Nations of the World in the Twentieth Century." Like much of the magazine's content, it represented an appeal to the Asian, Islamic and colonized peoples of the world to wake up and reform themselves so they could compete with the West. The cartoon shows pair of Indians are pulling a whip-wielding Englishman in a rickshaw, Greece is doing something to a bent-over Turkey, and China fast asleep. Uncle Sam peaks up over the globe on the right, while a polar bear watches alertly from above. This map turned up on Zerkala, a site that looks like it would be amazing if you knew Russian. This image below is apparently a Bukharan Trickster:

↧

↧

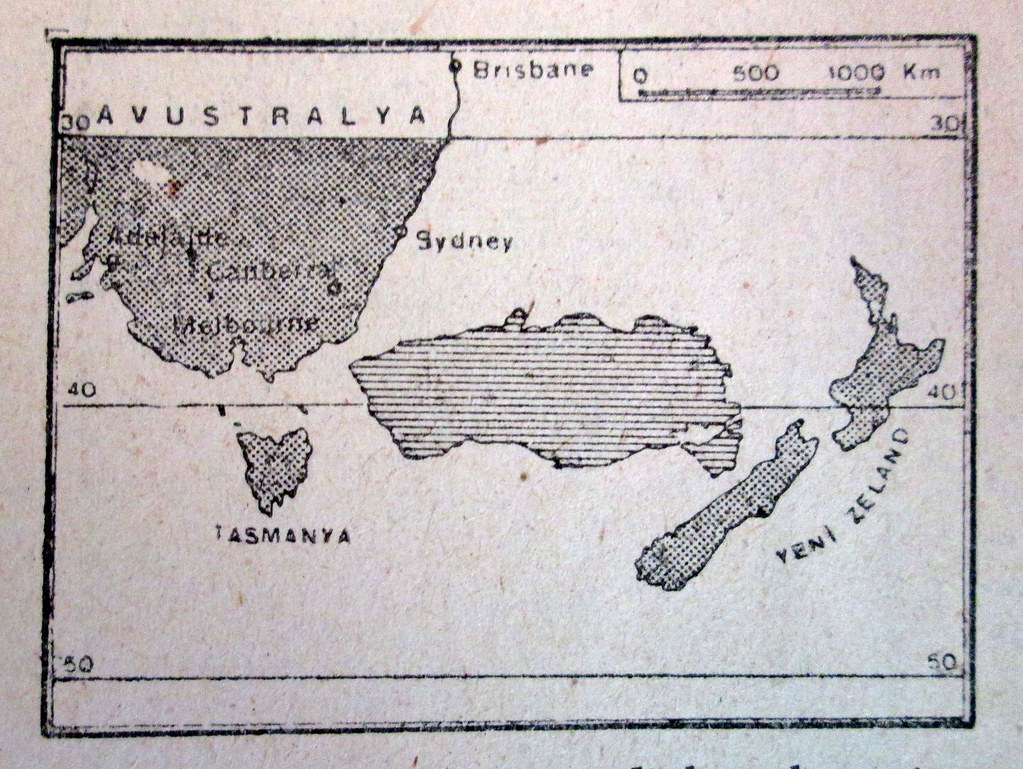

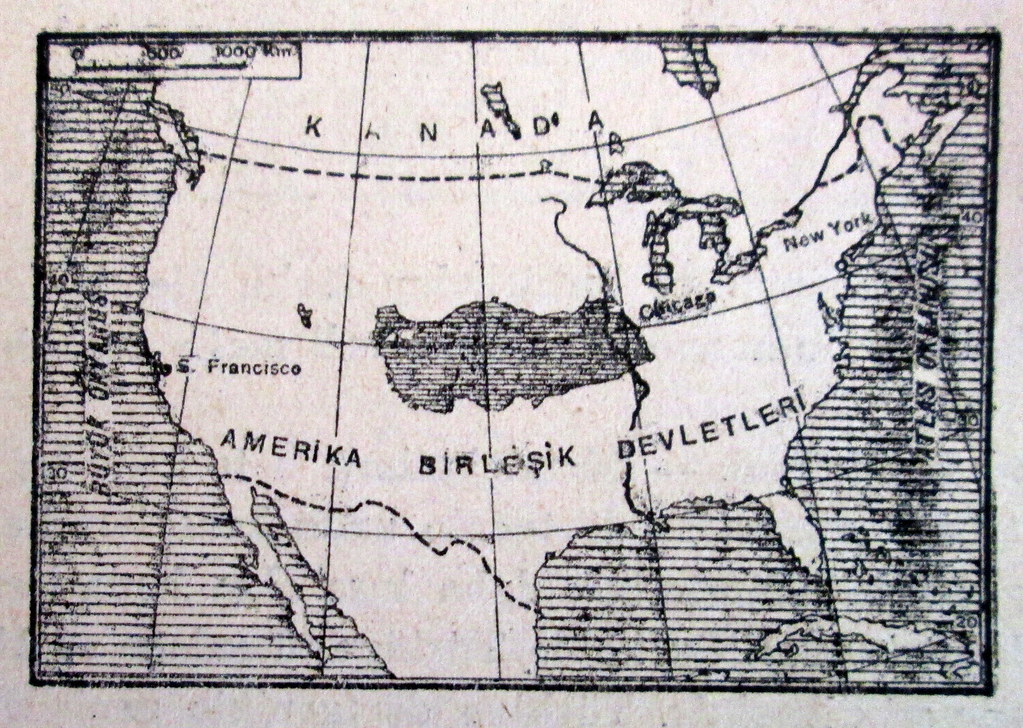

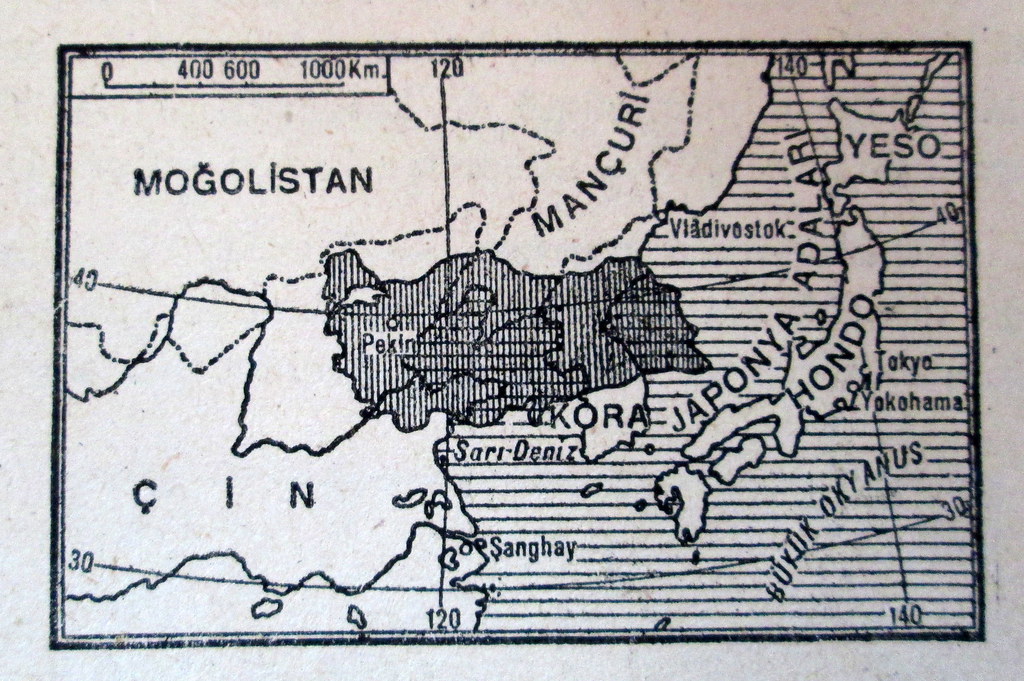

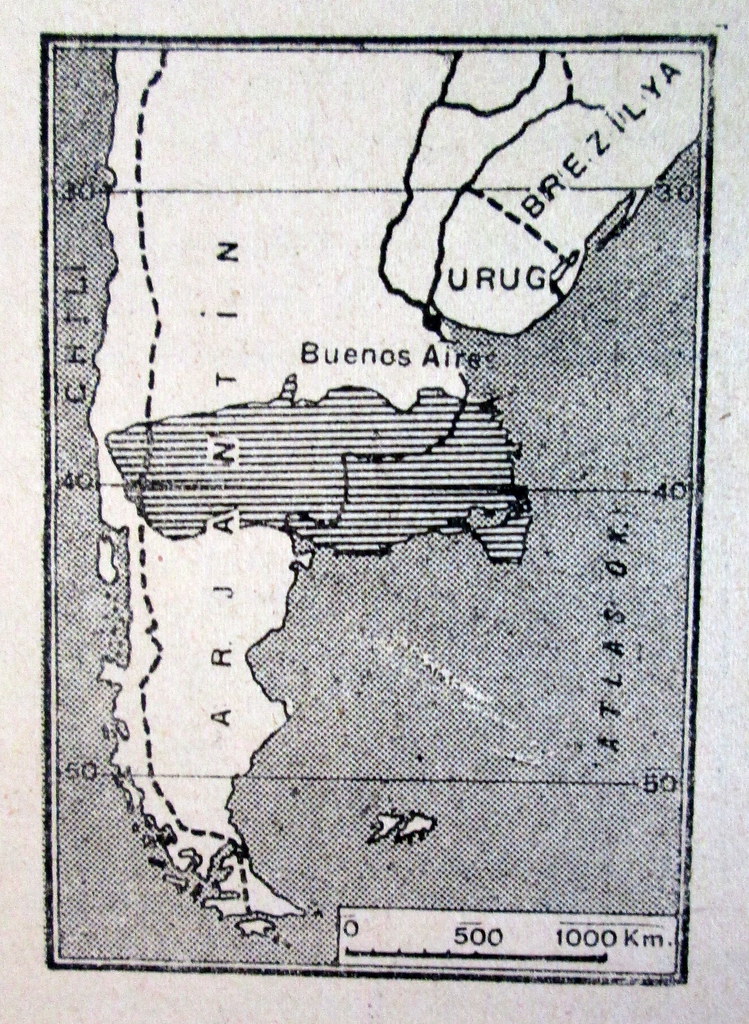

Turkey on the Move

How big is Turkey? These maps from Türkıye Coğrafya, a 1955 high school textbook from the Milli Eğitim Basımevi, help answer the question. The one-country-awkwardly-stuck-on-top-of-another-country style of comparative mapping has proved remarkably popular over the years, with recent examples including this map of the Pacific island of Nauru superimposed on Manhattan.

↧

From the Collection of Ibrahim Hakki Konyalı Part II

We're taking another break from maps to post a second set of random pictures from the Ibrahim Hakki Konyalı Archive (see the previous set here).

The caption says it all: the first day at the morgue's autopsy saloon, 5 Teşrinisani, 1928. (#438)

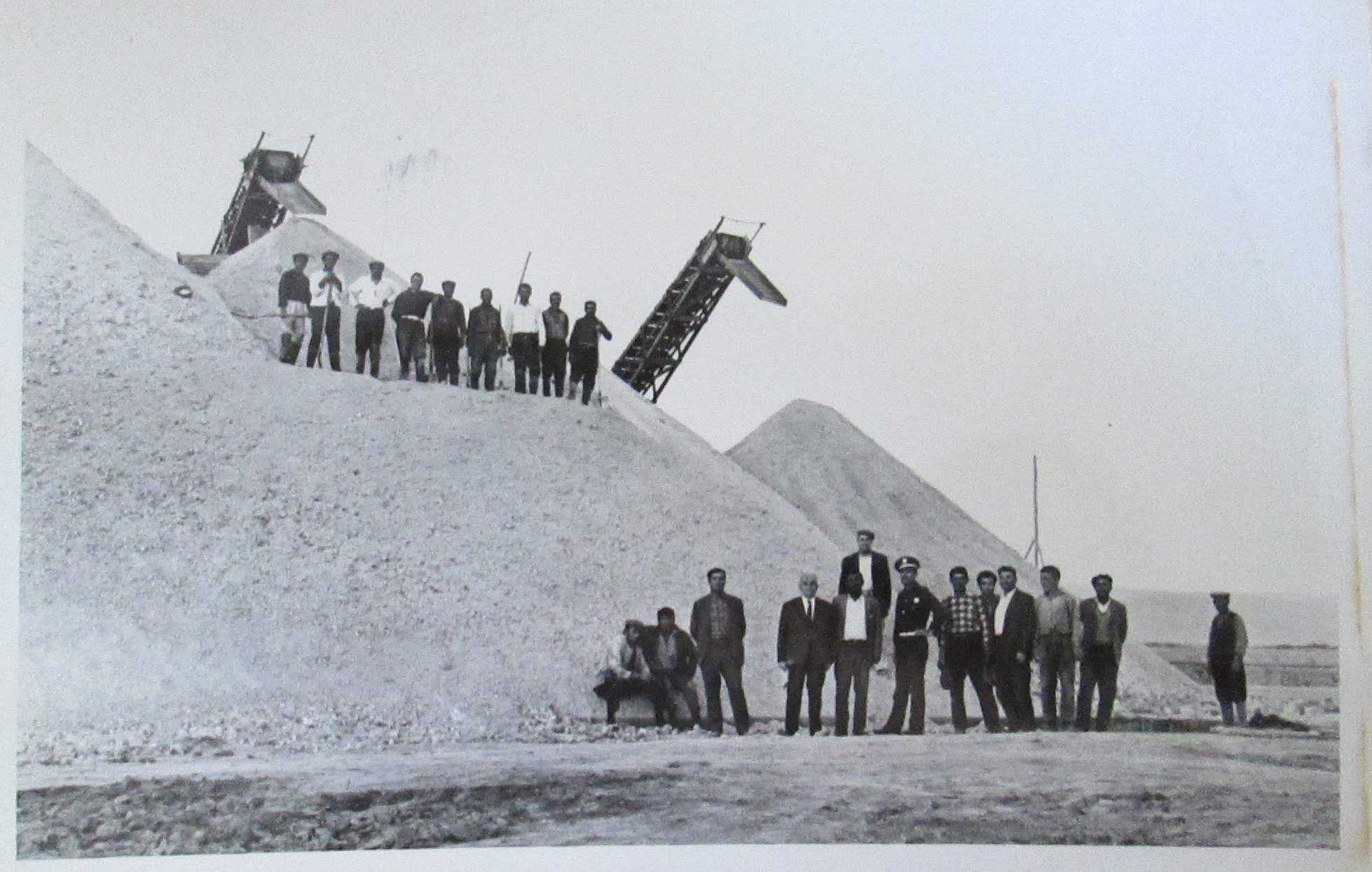

Salt extraction in the Salt Lake

And a series of mugshots of late Ottoman criminals. Anyone who wants to provide a transcription of the writing on the photos has my eternal respect.

First is a picture of Italian occupation troops in Konya after World War One. Books like "Birds Without Wings" have been faulted by historians for giving the impression that Italian occupations were fun, part of a broader trend toward treating Italian colonialism or Italian fascism as jovial alternatives to their more brutal counterparts. All that said, everyone in this picture seems to be having a good time. Some Turks, including a young kid, have showed up for the picture, and there's a guy with a cape. (Konyalı Archive, #676)

An undated picture from a Cumhuriyet Bayramı celebrations in Taksim. (#525)

One of the more inexplicable photos in the Konyalı archive, the caption simply reads "Grandsons of the goats who, according to mythology, discovered wine before the wine god Bacchus (Ereğli). [Mitolojiye göre şarap tanrısı baküs'ten evvel şarabı icat ettikleri iddia edilen kecçilerin torunları.]" (Konyali archive, #2885).

The caption says it all: the first day at the morgue's autopsy saloon, 5 Teşrinisani, 1928. (#438)

Salt extraction in the Salt Lake

And a series of mugshots of late Ottoman criminals. Anyone who wants to provide a transcription of the writing on the photos has my eternal respect.

↧

Mapping the Huntington-Stegosaur Debate at 20

Afternoon Map just launched its own Facebook page! Like us to see more maps...

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

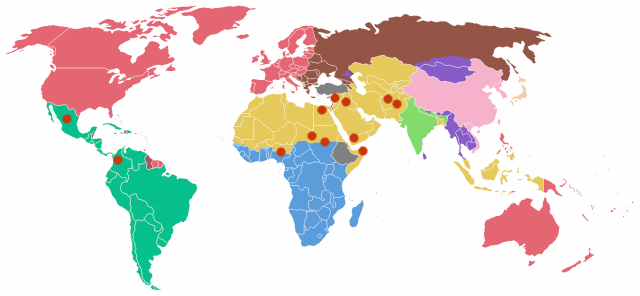

Almost exactly twenty years ago, Samuel Huntington predicted that conflicts in the coming century would occur along civilizational, rather than political or ideological lines. It was an analysis that even at the time seemed to have been inspired more by a Risk board than the real world, and subsequently many people have been understandably content to simply ignore it. Even after making this map, I thought perhaps more useful than actual analysis would be simply pointing out that you could create a more accurate model of global conflict with a child's drawing of a giant Stegosaurus. But this seemed too flippant in light of the damage done by people who do take Huntington seriously. And unfortunately, as this map sort of shows, his vision has been just accurate enough to encourage these folks.

![]() While Huntington named a number of different major civilizational groupings (shown at left), his focus was on the coming conflict between Western and Islamic civilizations. This map compares his hypothesis with data from the Uppsala Conflict Data Program that pinpoints world conflicts identified as causing 1,000+ deaths per year in 2012. If you're willing to ignore everything else going on in Afghanistan and post-US-withdrawal Iraq, then it appears two of these eleven conflicts fit Huntington's prediction, as well as another two, in Nigeria and Sudan, that he would say are between Islamic and "African" civilizations, whatever that means.

While Huntington named a number of different major civilizational groupings (shown at left), his focus was on the coming conflict between Western and Islamic civilizations. This map compares his hypothesis with data from the Uppsala Conflict Data Program that pinpoints world conflicts identified as causing 1,000+ deaths per year in 2012. If you're willing to ignore everything else going on in Afghanistan and post-US-withdrawal Iraq, then it appears two of these eleven conflicts fit Huntington's prediction, as well as another two, in Nigeria and Sudan, that he would say are between Islamic and "African" civilizations, whatever that means.